From Wednesday, June 28 to Sunday, July 2, the Anglican Church of Canada held its 2023 General Synod, the triennial meeting that brings together Canadian Anglicans to make decisions on matters of churchwide governance. I followed along from afar as best I could while studying in Wittenberg, thanks mostly to my colleague the Rev Dr Jesse Zink’s excellent Medium blog and occasional updates in the Anglican Journal.1 For me, then, checking up on the work of General Synod happened to be juxtaposed to reading and thinking about the German Reformation. I hope you are not all sick of the very Reformation-theology-focused content of my last few pieces. In my defense, this is, after all, what I study as a PhD student – and the last six weeks of sustained study in Wittenberg have meant that Luther et al have been very much on my mind. And in this case I think the juxtaposition was a fruitful one. The Reformers are helpful in thinking about church order, because when faced with the challenge of shaping the life of the newly formed Protestant churches, they consistently sought to order church governance towards the Gospel of Jesus Christ as they understood it.

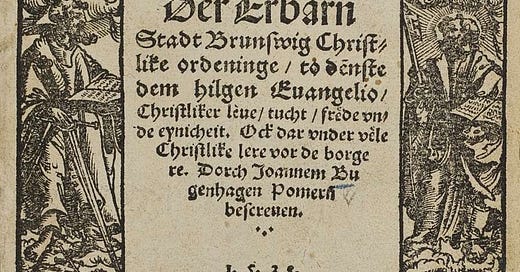

I should be clear that I am well aware of the importance of the less-than-dramatic work of institutional maintenance, and do not condemn careful attention to the nuts and bolts of church governance. Quite the opposite! One of the most interesting facets of the Reformation to me is the way Reformers sought to institutionalize Reformation theology as the Reformation moved from popular movement to established church. Kirchenordnungen (church orders) were put together in Lutheran areas to govern the life of the new churches: church structure, worship and liturgy, catechesis and devotional life, church discipline and more; Johannes Bugenhagen, pastor of the Stadtkirche in Wittenberg, was a particularly prolific author of these documents. In England, of course, we have various Acts of Parliaments, the prayer books, Cranmer’s abortive attempt at ecclesiastical law reform, the 1603 canons, and various other official means of shaping the life of the newly independent Church of England. Everywhere where Protestantism took root, the Reformers realized that sustaining the life of the church required careful attention to matters of order and organization that seem, at first blush, far removed from Luther’s theological breakthroughs. It’s also worth saying explicitly that the Reformers neither solved all questions of church order perfectly nor lived in a golden age of perfect piety. There was no time in church history when all the laypeople were pious, all the clergy were laser-focused on the Gospel, and all disputes over governing the church were related only to substantive theological matters. A look at early modern visitation records is sufficient to put any optimism on that front to rest for the sixteenth century.

But all the same, the Reformers’ institution-building work gives us a helpful question to ask when we look at our own approaches to church governance: do our discussions about church governance focus on how to best facilitate the proclamation of the Gospel? I’d propose that we learn from them a criterion for assessing good vs. poor church governance: good church governance is ordered clearly and explicitly towards the Gospel; poor church governance is not. This criterion is always important, but I think it is especially important now for Anglicans in North America. Speaking as a TEC priest serving in the ACC, both our churches are in situations of crisis, bleeding numbers and resources. As a result, we are no longer able to address as many secondary or tertiary matters as we once comfortably could. We are forced by the exigencies of reduced capacity to decide what most matters to us, what is most worth our time and attention. Indeed, even if we do not decide explicitly, we end up doing so de facto by what we choose to spend the most time on. And so it seems to me worth asking, here specifically for the Anglican Church of Canada: in the precious five days every three years that our highest governing body meets, are we facing the crisis head-on and focusing ourselves clearly and unambiguously on the Gospel upon which the church stands or falls?

Unfortunately, I do not see how we can answer this question in the affirmative.

If Zink’s General Synod diary and the Anglican Journal articles are any guide, it seems that the church spent an enormous amount of its floor time on remarkably unimportant matters and failed almost entirely to address the core question of how to facilitate Gospel proclamation in the light of our current ecclesial crisis. A great deal of time was taken up by what Zink calls “the rah-rah church agenda,” namely, presentations from various Anglican organizations about the good work they do. And when the church actually got down to making governance decisions, what did it focus on? Not one but two days of debate involved extended consideration of whether to allow primates of the Anglican Church of Canada to serve beyond the mandatory retirement age of 70 (our current primate will turn 70 less than a year before the 2025 General Synod meeting). Without denying the personal importance of this question to our current primate, was this matter so vital to the health of the church as a whole that it needed two days out of five? A great deal of attention was also devoted to a controversial Israel-Palestine resolution and to issues of climate justice. I have rather conventional lefty views on both these issues, but I doubt that the world is waiting with bated breath to hear what the Anglican Church of Canada thinks about carbon-zero or peace in the Middle East. I am willing to be convinced otherwise, but even when I agree with the substantive position I struggle to see the value of statements like these. There was also a debate about a resolution to make it more difficult for ministers ordained in other traditions to serve in the ACC – a resolution which was largely seen as an anti-ANiC move but would have had consequences for longstanding ACC cooperative ministries involving other denominations, had not it been amended into near-irrelevance during debate. To put it bluntly, in a moment where a combination of principle and necessity is leading our church into greater ecumenical engagement, I do not quite understand why making it harder for people to serve in the ACC is worthwhile.

I do want to try to be fair. It’s not that there were no substantive issues discussed: there was, for example, a long debate on authorizing liturgies for gender transition, which (whatever your position on the resolution) is clearly significant. I do hope that there were other consequential questions taken up too. But by and large they seem not to have dominated the floor time. What’s more, the most basic thing that seems to have been missing was any recognition that our church is in a profound crisis. The church statistician submitted a grim report to General Synod about our church’s future, but per Dr Zink not a minute of floor time was devoted to discussing it. (I’d add that MAiD, an issue of justice about which the Anglican Church of Canada could actually have something to say to its members with concrete effects on their behavior, was similarly ignored). Zink describes talking with a fellow attendee who described the mood of a Synod presentation by saying that “it was almost offensive how upbeat it was.” I confess that I am not surprised; as I’ve written before, I fear that our church too often struggles with honesty, adopting a cheap optimism rather than taking stock of the challenges of the current moment. As far as I can tell, the this is what happened at General Synod: the dire realities of our church’s present and likely future were ignored in favor of an agenda focused heavily on employment policy and on justice questions about which the Anglican Church of Canada can do very little other than pass resolutions.

And this brings me back to the curious juxtaposition I noted at the beginning of the piece, between my studying the church-building efforts of the Reformers and observing General Synod. The Reformers’ efforts at establishing and maintaining Protestant churches had the Gospel at the heart: the goal was to produce modes of church life that fostered the proclamation of the Gospel, the good news of the free gift of salvation through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. They may have done so more or less successfully, but the goal was clear. Is the work of church governance in the Anglican Church of Canada ordered around that same goal? I don’t see how one could answer affirmatively on the basis of our last General Synod. And for my US readers, I doubt strongly that the Episcopal Church does much better.

Here, of course, I am treading familiar ground for readers of this Substack. I worry sometimes that I end up being repetitive when I talk about our discipleship crisis, our refusal to grapple with decline, our failure to prioritize doctrine and holiness in our clergy, our anti-theological bias — in short, our general lukewarmness towards the things of God. But I don’t want to end with complaining about how bad things are.

No, I want to say this to clergy and lay Christian leaders involved in governance in Canada and beyond: We can live differently than resigning ourselves to managing an institution in precipitous decline while tiptoeing around the reality of that decline. We have something more exciting than passing resolutions that accomplish very little while ignoring the elephant in the room of coming collapse. In the Gospel of Jesus Christ, we have something transformative, exciting, worth staking your life on! This has been one of the most precious consolations of the summer in Wittenberg for me: the reminder of how profoundly exciting the Gospel is! Jesus is so very loving, so gracious to us. We worship such a good God! What a privilege to get to serve him as a minister!

It’s not that we have to orient church governance towards the Gospel or have to engage in real discipleship or evangelism if we want our church to survive. No! It’s that because of what Jesus did for us, we get to use his person and work as a measuring stick for how we order our ecclesial common life, we get to invite those who know him and those who do not into ever-deeper relationship with him and each other. This, it seems to me, is a reason that enduring the unglamorous work of church governance in struggling institutions is thoroughly worthwhile: because it too can be about Jesus and how our church might more abundantly and boldly proclaim the saving Gospel. And my hope for all of us is that God might use us to make our governance much more clearly oriented towards Jesus, not least so that we can find real joy and even excitement in the work.

As I prepare to return to Canada and my service in the Canadian church, I want to keep this question that emerged so powerfully from my studies this summer front and center: how can I foster in myself and others in our church a real excitement for the Gospel, and order all of my work in the church towards its proclamation? I’ll be excited to continue that conversation with you in the coming weeks and months.

To be clear, while I am dependent upon Jesse Zink’s blog and the Anglican Journal for keeping me up to date on General Synod, the analysis that follows is mine and mine alone, with which the sources I used may or may not agree.

How can you say the world is not dying to hear what mainline churches have to say about the latest most progressive social-justice issue? How can you be so cruel?! You must have heard in ALL the media about our latest UCC synod. Such media coverage!