On the Weight of Ministry

Thinking about ministry & ministerial misconduct with the classical Anglican ordinal

Today is the first of the Advent Ember days, one of the four periods that Anglican churches set aside during the year for prayer and fasting for those preparing for ordination. I take the Ember days as an opportunity not just to pray for those who will take on Holy Orders but also to reflect upon my own ministry. One of the ways I do this is to read through ordinals, both the ordinal with which I was ordained (that of the Episcopal Church’s 1979 BCP) and the classical Anglican ordinal.

I was reading through the classical ordinal this morning, and in particular spent some time with the bishop’s address delivered after the Gospel reading in the ordination of priests. In reading it, I was immediately struck by how strongly it expresses the weight of ministry. I mean this in a few senses. For one, it expresses the awe-inspiring truth God has chosen mere human beings to be his instruments of salvation, using the preaching of the Word and administration of the sacraments as means to create faith when and where he will (Augsburg Confession Art V). To be sure, it is God alone who regenerates and illuminates, yet he ordinarily chooses to do so not by direct revelation of himself or by the teaching of angels but by the ministry of human beings. This is an amazing thing!

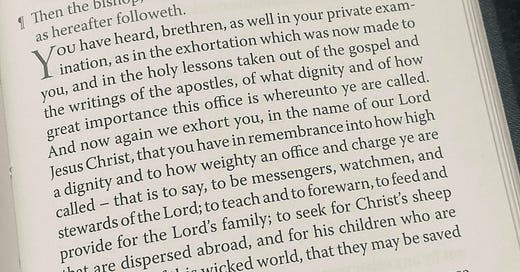

The beginning of the bishop’s address hits on exactly these themes:

You have heard, brethren, as well in your private examination, as in the exhortation which was now made to you, and in the holy Lessons taken out of the Gospel and the writings of the Apostles, of what dignity and of how great importance this office is, whereunto ye are called. And now again we exhort you, in the Name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that you have in remembrance, into how high a dignity, and to how weighty an office and charge ye are called: that is to say, to be messengers, watchmen, and stewards of the Lord; to teach and to premonish, to feed and provide for the Lord's family; to seek for Christ's sheep that are dispersed abroad, and for his children who are in the midst of this naughty world, that they may be saved through Christ for ever.

This sense of the importance of the pastoral office is, of course, no sixteenth century innovation. Here is Gregory Nazienzen in the fourth century on pastoral care, from his Oration 2:

But the scope of our art is to provide the soul with wings, to rescue it from the world and give it to God, and to watch over that which is in His image if it abides, to take it by the hand if it is in danger, to restore it if ruined, to make Christ to dwell in the heart by the Spirit, and, in short, to deify, and bestow heavenly bliss upon, one who belongs to the heavenly host.

Now, passages like this one of Gregory’s may risk (at least by sixteenth century evangelical standards) attributing to the human being what is properly God’s work, but this sense of the intense seriousness and importance of pastoral ministry is a commonplace throughout Christian history. Many would agree with Gregory the Great that pastoral care — as he calls it, “government of souls” — is the “art of arts.”

But there’s another sense in which the office of ministry is weighty according to the classical ordinal. It is weighty in that, precisely because it is so important, the consequences of failure are heavy.

Thus the bishop’s address continues:

Have always therefore printed in your remembrance, how great a treasure is committed to your charge. For they are the sheep of Christ, which he bought with his death, and for whom he shed his blood. The Church and Congregation whom you must serve, is his spouse and his body. And if it shall happen the same Church, or any member thereof, to take any hurt or hindrance by reason of your negligence, ye know the greatness of the fault, and also the horrible punishment that will ensue. Wherefore consider with yourselves the end of your ministry towards the children of God, towards the spouse and body of Christ; and see that you never cease your labour, your care and diligence, until you have done all that lieth in you, according to your bounden duty, to bring all such as are or shall be committed to your charge, unto that agreement in the faith and knowledge of God, and to that ripeness and perfectness of age in Christ, that there be no place left among you, either for error in religion, or for viciousness in life.

This rather grim warning about the consequences of failure in the ministry is, of course, entirely Scriptural. One thinks of Paul’s admonition to Timothy not to ordain anyone carelessly, James’ declaration that not many should be teachers because teachers will be liable to a stricter judgment, or Jesus’ words in Matthew 18: “If any of you put a stumbling block before one of these little ones who believe in me, it would be better for you if a great millstone were fastened around your neck and you were drowned in the depth of the sea.” At Yale Divinity School, where I attended seminary, there are millstones set into the campus quad. I would think of this verse often when I walked upon them, and the weight — in the sense of the eternal consequences — of ministerial failure.

Small wonder that Gregory Nazienzen excuses his refusal to take on the work of ordained ministry with a plea about its nigh-impossible difficulty1 or that Gregory the Great complains about those who without knowledge or wisdom willingly take upon the role of “physicians of the heart,” even though they would never dare to be “physicians of the body” without understanding of medicine. Indeed, one of the scariest things about being a pastor is reckoning with the fact that you will, at some point or another in your ministry, be an impediment — please God just a temporary one — to the Christian life of someone under your care. Whether through ignorance (even ignorance that isn’t your fault), an ill-timed sharp word in a low moment, a sermon that was what 99% of your flock really needed to hear but that remaining 1% really didn’t, to say nothing of deeper and more profound sins, you will hurt someone whom you have promised God to shepherd. If, as Luther says, the life of the Christian is one of constant repentance, this ought be even more true of ministers — for there is no way to live this vocation without constantly throwing yourself on the mercy of almighty God.

Given this twofold sense of the weight of ministry — weighty as in honorable and important; weighty as in a millstone around your neck — the bishop’s address goes on to discuss how one can carry it out. The address begins by noting that mere humans are not capable of an office “of so great excellency and of so great difficulty” themselves; instead, “will and ability is given of God alone.” Thus “ye ought, and have need, to pray earnestly for his Holy Spirit.” Constant prayer to the Father for the Spirit by the mediation of the Son, the address says, the basic posture of the ordained life. Along with it, the address calls the ministers to abandon worldly cares and studies and instead commit to “daily reading and weighing of the Scriptures.” These are the means — awareness of ones incapacity, prayer for the Spirit, immersion in Scriptures — by which “ye may wax riper and stronger in your ministry.”

I think that this address has a lot to teach us today about the nature of ministry and of ministerial misconduct. And in fact I hope and pray for a recommitment in contemporary Anglicanism to what it teaches: the dignity and danger of ministry and the necessary means for undertaking it.

First, on the nature of ministry, I would love us to recover a proper understanding of the amazing end at which ministry aims. In training in pastoral care especially, rather than emphasizing ministry as about being God’s instruments of the present justification and sanctification and eternal glory of the people committed to our charge, often it is talked about as having to do with social uplift and a sort of vague, nontheological pastoral accompaniment. Now, don’t get me wrong: the duties of the ministry absolutely involve addressing social injustice and being a gentle, listening presence to people in crisis. But they don’t stop there; being a minister is not just being an ersatz political organizer or therapist. It it about being an ambassador of Christ, announcing the Gospel of grace, proclaiming the good news of what God has done for us in Christ Jesus and calling all to be reconciled to God! We are not just part of the spiritual genus of the family ‘helping professions.’ Now, this should not mean inappropriate levels of deference to clergy themselves; it is the work of ministry more than the person of the cleric that has such amazing dignity. Nor should it be is a reason for pride, for the salvation of which we are instruments is entirely God’s, and without his Spirit we accomplish nothing at all. But it should be a reminder of the incredible, eternal seriousness — the weightiness — of what we do.

Secondly, and relatedly, I think that we need to retrieve a proper awareness of the weightiness of ministerial sins. It strikes me that while the 1979 ordinal certainly talks about the dignity of ordained ministry — indeed, arguably elevates ministers significantly more than the classical ordinal2 — the danger of failure appears not at all. The (robustly Scriptural) idea that ministers who commit gross misconduct risk their own souls and those of the people under their charge shows up nowhere at all. And I wonder if this has something to do with some of the failures in contemporary Anglicanism to deal with the vile sin of clergy misconduct.

Specifically, it seems to me that we often miss the seriousness of clergy wrongdoing. Sins around doctrine are barely considered sins at all; the idea that clergy could or should be disciplined for willful, unrepentant doctrinal error is not infrequently criticized. And this despite what Scripture has to say about the dangers of false teachers, the real possibility of such teachers leading sinners for whom Christ died into ruin and shipwreck of their faith! As I’ve written before, the idea that clergy should be called to particular holiness of life is often pooh-poohed as well, despite the fact that this is clearly established in Scripture as a vital criterion for ministry. In particular, the idea that clergy sexual lives should be held to standards other than the prevailing secular ones of consent of all parties involved and noncoercion is often treated as oppressive.3

But even about those matters that everyone agrees are wicked — clergy sexual abuse, say — one of the things that I have found most frustrating is our continued refusal to reckon with just how serious they are. When a scandal breaks, our leaders often default to the language of secular crisis communications and the sort of self-justification that would make any CEO proud. Imagine how different it would feel if a bishop or archbishop called their clergy to a month or a year of fasting and prayer in response to our church’s abject failure to care for those under our care, and made that call concrete by spending hours every day on their knees in sackcloth in their cathedral? Surely the eternal life of both victims and perpetrator — to say nothing of one’s own! — is worth such prayer. Too many bishops continue a culture of covering up and protecting abusive clergy, forcing laity and junior clergy to use whisper networks to keep themselves and their people safe.4 Imagine if such clergy sin was genuinely seen as an emergency which, for the sake of the souls of everyone involved (including the offending cleric) required immediate and strict discipline. It is striking to me that most of my clergy misconduct training was carried out in the register of professional norms and best practices for the caring professions. Given that we seem unable to even attain that level of decency, perhaps this is needful as a first step…but surely as a church we should have more to say than this!

Now, I want to be careful here. I don’t want to suggest that talking about the deep seriousness, the millstone-level weightiness of clergy misconduct in theological terms is a cure-all for our continuing abuse problem. I have no indication that back when Anglican clergy heard this bishop’s address at their ordinations, they were less likely to abuse than contemporary clergy are. As a church historian, I am all too aware that wicked clerics are a constant problem. And, frankly, our awareness of the profound evil of clergy abuse and especially sexual abuse is something that we have come to appallingly late as a church. In fact, this awareness still insufficiently reflected in our procedures for handling clergy misconduct. But what I long for — and what I see the church still largely failing to do, with a few honorable exceptions5 — is a combination of a modern understanding of the nuances of abuse and awareness of the issues of power and trauma that make reporting difficult with this historic awareness of clergy failure as spiritual disaster.

And so, this Ember week, I commend the entire classical Anglican ordinal to your reading and particularly the bishop’s address in the ordination of priests. Especially for my fellow ordained clergy, I think it is bracing but edifying reading. And it is my hope that if reading it moves you to reflection on ministry’s dignity and danger, it would all the more move you to the tools for ministry it offers: a realization of one’s own incapacity, fervent prayer for the gift of the Holy Spirit, and daily meditation on Scripture. May God indeed use all these means to train us up in the “art of arts” and make us instruments of his abundant grace.

We need not be naive about Gregory’s rhetorical performance of humility here to recognize the reality to which it points.

This is especially the case in the service for the ordination of bishops, which as Bryan Spinks has argued adopts a much more monarchical conception of the episcopate than either the classical ordinal or many other contemporary Anglican liturgies. But I think that the language of the ordination formulas in all three services also tends towards an ‘ontological’ view of ordination which I worry inscribes precisely the sort of difference between ‘lay’ and ‘clerical’ states that Luther criticizes in On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church.

Of course, consent and noncoercion are vital parts of any Christian sexual ethic — and this is something that Christian sexual ethics have often failed to recognize. But this does not mean that they are a sufficient sexual ethic for Christian living.

I, frankly, don’t feel able to say much about this publicly at this point, but suffice it to say that one of the real shocks of ordained ministry for me has been just now necessary such networks have been, for me personally and for those I have needed to keep safe.

For example, in the Episcopal Church: while I am still unsure whether or not Bishop Singh should have been deposed rather than an accord reached, I am thankful that the accord is both quite demanding in terms of what would be required for the bishop to return to ministry and actually somewhat theological. I am also thankful that it was made public. I hope that this is a beginning of a better trajectory under Presiding Bishop Rowe’s leadership, after the failures under Presiding Bishop Curry’s.

As someone who has heard a few too many sermons along the lines of “Ministry is really hard, so be nice to me, your pastor”—I’m so glad this piece didn't go the direction I was halfway expecting. Thank you for writing this.

A fitting Ember reflection for Advent III week. The Ember week falling in Advent III surely must have been an influence on why Cranmer revised the Collect for Advent III to be as it is, no? As a layman, your bracing exhortation here awakens me to how to pray for my clergy. Do I pray insipid prayers about non-descript "blessing" or do I pray against spiritual shipwreck and for holiness and innocence of life? Thank you!