As I expect most of my readers know, my ‘day job,’ as it were, is a PhD student in ecclesiastical history. While I share some of my findings here, I don’t actually talk very much about the process of historical research. So I thought it might be interesting to share an example of a recent finding I made, and how I made it. I’ll note that I am going to go through how I actually did this research, not what would have been the most efficient way to do it. This is definitely still something that I am learning how to do well.

For a conference paper I presented last month at the Society of Reformation Studies conference at Cambridge, I was investigating references to disputes in the early decades of the Wittenberg reformation in Jacobean English writing. I came across one interesting example in John Boy’s postil (sample sermon collection), specifically his analysis of the epistle for Septuagesima Sunday. This text was regularly republished in the early seventeenth century and seems to have been fairly widely used as an aid to sermon preparation by Jacobean clergy. The text itself, incidentally, I was able to access via Early English Books Online — a comprehensive although not complete subscription database of digitized early printing in England.

As you can see, Boys uses Andreas Karlstadt (“Carolostadius”), an early ally of Luther in Wittenberg who fell out with him over the pace of reform and eucharistic doctrine, as an example of what it is to have the right goal but use the wrong means in religious matters. Boys analogizes Karlstadt’s wrong use of means to Puritans in his day, who seek to obey the Gospel but do so wrongly. When I first read this text a while ago for another conference paper, I thought this reference was interesting and made a comment on the PDF — and now I had the chance to go back and take a closer look.1

I wanted to establish where Boys got this picture of Karlstadt from. There is no marginal citation for the reference to Karlstadt, although there is a somewhat mysterious Melanchthon reference above (“Melanchthon. in loc tom .4. sci .236.”) for the general principle of attending not just to the ends but also the means.

I knew that Boys referenced Foxe’s Acts and Monuments (aka Foxe’s Book of Martyrs) frequently throughout his work as a whole. So Foxe seemed like a good place to start. Given sixteenth century citational practices, it would not have been shocking if there were other unacknowledged borrowings from Foxe besides the ones that Boys explicitly cited. Fortunately, all four editions of the Acts and Monuments published during Foxe’s lifetime have been digitized by the Digital Humanities Institute of the University of Sheffield. I was able to text search to find how Foxe discusses Karlstadt. I discovered after a few tries that Foxe used the same version of Karlstadt’s name as Boys, Carolostadius. But the references to Karlstadt in Foxe didn’t really match up with Boys’ reading of him. Indeed, Boys was significantly more negative in his portrayal of Karlstadt than Foxe. Especially in the later editions, Foxe’s discussion of the Luther-Karlstadt controversy was concerned mostly about exculpating Luther for a seemingly overly-permissive (from Foxe’s perspective) view of images. So Boys did not seem to be dependent on Foxe for his portrait of Karlstadt and his dispute with Luther.

Next I checked Luther’s church postil, Luther’s commentary on the appointed epistles and gospels. This was another text which I knew that Boys used not infrequently, and it wouldn’t have been shocking to me if Luther mentioned Karlstadt in it. Here I just checked an old English translation, knowing that if I found anything that seemed like a match I would need to go look at the early German and Latin versions. But Luther’s treatment of the Septuagesima Sunday epistle didn’t mention Karlstadt at all. So this didn’t seem to be a terribly likely source either.

This brought me back to the Melanchthon reference for that general principle of the necessity of the careful consideration of means as well as ends.2 The citation was for a paragraph above the Karlstadt reference, but it was the closest marginal citation and seemed worth tracking down. But what Melanchthon work was Boys citing? I wasn’t quite sure; I’m not an expert on Melanchthon’s corpus. My first guess was that some editions of Melanchthon’s greatest work, his Loci Communes, might have divided its topics into separate books. This would make sense of the “tom .4.” reference. So I pulled up VD16, the (nearly complete) database of sixteenth century German prints hosted by the Bibliotheksverbund Bayern with links to available digitizations, to find some digitized late 16th c. printings of Melanchthon’s Loci to see if they were indeed organized in this way. No such luck.

At this point, I probably should have spent a little more time digging into what this reference could mean.3 But instead I decided to switch gears and, rather than trying to decipher the reference, look at Melanchthon’s corpus and try to figure out what texts Boys might be quoting from. I knew that for his postil, Boys drew frequently upon other postils as well as Scriptural commentaries dealing with the texts in question. So, did Melanchthon have such a postil?

To answer this, I went to the Corpus Reformatorum, which remains the critical edition of Melanchthon’s works, and found that he did! My excitement quickly faded when I realized that his postil was merely a commentary on the Gospel texts rather than both the Gospel and Epistle. So this was unlikely to be the source. But it turns out that Melanchthon did have a commentary on 1 Corinthians, the epistle from which the Septuagesima Sunday epistle reading was drawn. This seemed worth investigating to me.

This commentary is printed in Corpus Reformatorum vol. 15. When I turned to 1 Corinthians 9, the chapter from which the Septuagesima epistle was drawn, I had my eureka moment.

The discussion of Karlstadt in Boys’ text was in fact a translation (with a few modifications) of Melanchthon’s discussion of Karlstadt in his exegesis of 1 Corinthians 9! (The general principle that Boys more explicitly cites is also found earlier in the text.)

So at this point I was able to fairly confidently conclude that Boys got his picture of Karlstadt from Melanchthon’s 1 Corinthians commentary (the only other possibility was that Melanchthon repeated this description of Karlstadt verbatim in another publication, but I judged this unlikely). However, my work wasn’t done. I now needed to return to the Melanchthon citation to figure out what specific edition of Melanchthon’s Boys used for this reference.

I knew Boys had gotten the Karlstadt discussion as well as the principle about attending to means (which alone was explicitly cited) from Melanchthon’s First Corinthians commentary. But the marginal reference clearly wasn’t to a standalone printing of that commentary. This meant that the commentary must have been included in a collection of Melanchthon’s works, and that must be how Boys found it. And so what I was looking for was a fourth volume (“tom .4.”) of some edition of Melanchthon’s collected works. A little more work with VD16 brought me to a likely candidate, the Omnium Operum Reuerendi Viri Philippi Melanthonis, Pars Quarta, first printed in Wittenberg in 1564.

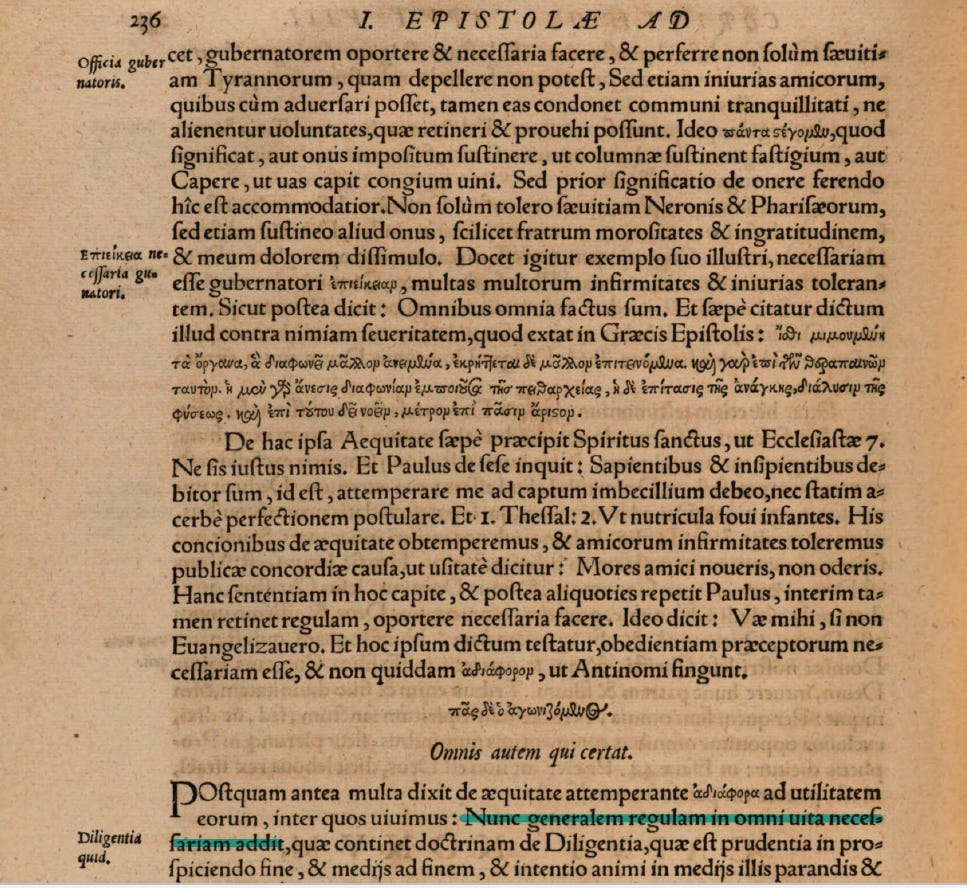

Rather marvelously, a huge number of the works in VD16 have free digitized versions accessible via links from the database.4 This was one of them, thanks to the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. I turned to page 236, the reference given in the marginal citation. And sure enough, there we found the principle about running rightly that Boys cites. This is the exact source that John Boys used!

And then, on the page following, came the discussion of Karlstadt that was the focus of my inquiry. This was the answer to my question: John Boys looked at a page more or less identical to this one some four hundred years ago to translate its description of Karlstadt’s error for inclusion in his own postil. This is the sort of thing that gets me really excited.

At this point, I had found what I needed: I had proved that Boys’ discussion of Karlstadt in his analysis of the Septuagesima Sunday epistle was taken from Melanchthon’s First Corinthians commentary, and that Boys had found this commentary in the fourth volume of an edition of Melanchthon’s collected works.

Of course, this didn’t mean that the paper itself was ready to go. In fact, all this just amounted to a paragraph in the final conference paper. Now I had to actually draw conclusions from this and the other references to Wittenberg Reformation disputes I had found — and since I’m hoping to publish that paper at some point, I won’t spill the beans now.

Even if I am holding out on revealing the ‘big picture’ conclusions, I hope this was enjoyable — and not just for the interesting (at least to me) result that a Jacobean writer was reading and using Melanchthon for his picture of the Wittenberg Reformation.

As an illustration of how historical research works, I think it shows just how much recent advances in digitization have transformed research. It is truly amazing to be able to word-search Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, or to have access to a searchable database of sixteenth-century German printing.5 And even more basically, it is not long ago that accessing the Boys postil and the volume of Melanchthon’s collected works would have probably required visits to multiple libraries, quite possibly in different countries. Only the Corpus Reformatorum would have been immediately available at most decent-sized research libraries. Now all this digitized material was quite literally at my fingertips! It’s really quite astonishing.

But for all the real gains that such technical advances have given us, at the end of the day this sort of research is, as it has always been, a set of very satisfying puzzles to solve or mysteries to unravel. Which, I expect, is part of why I enjoy it so much.

Along with or in place of such PDF comments, I also take notes in a database (I use Obsidian) so I have my notes in one text-searchable place rather than needing to go back and dig through PDFs.

I probably should have started here, in fact, but since the Melanchthon reference was somewhat confusing and wasn’t a direct citation for Boys’ discussion of Karlstadt, I started with Foxe and Luther given their prominence as sources in this text.

As I said, this is an account of how I actually did this research, not how in retrospect I should have.

It’s really hard to overstate how cool this is. Both German and Swiss libraries have put a lot of resources into digitizing their early prints and making them available This work isn’t complete yet but a great deal has been done. And they’re available for free, unlike the digitized material in Early English Books Online which requires a subscription.

There is something similar for English printing, the online version of the English Short Title Catalogue. It has, however, been offline due to a cyberattack at the British Library back in October 2023, to the consternation of those of us who work on this material.

Okay, that's awesome fun! 🤓