Good Friday & Easter with the Book of Homilies

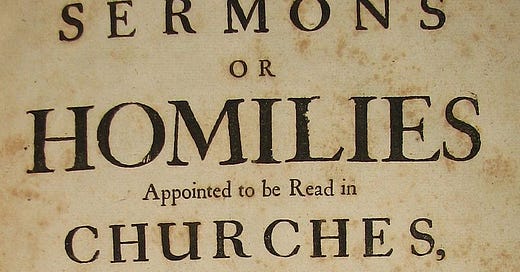

The two Books of Homilies, set forth in 1547 and 1563 (with a final sermon appended in 1571), are undoubtedly the most neglected of the formularies of the Church of England. They were, as the title suggests, two books of sermons compiled to teach the doctrine of the reformed Church of England. The first was put together by Archbishop Cranmer under Edward VI; the second book by Bishop Jewel under Elizabeth I. Originally, all clergy not licensed to preach were required to read from the Homilies in lieu of composing their own sermons; the 1603 canons required every parish church to own a copy. But despite that canon and the Homilies’ endorsement by the Articles of Religion (Article 35 says that the Books of Homilies “contain a godly and wholesome Doctrine, and necessary for these times” and thus calls for them “to be read in Churches by the Ministers, diligently and distinctly, that they may be understanded of the people”), the Homilies would come to be largely neglected. Indeed, in the mid-nineteenth century, the Prayer Book and Homily Society complained that by the early 19th c. they “had fallen into comparative oblivion, and were unattainable by the mass of the people.” Perhaps they overstated the case; we do find evidence of their continued import in the thought of someone like John Wesley, who regularly quoted them.1 And to be fair, perhaps some might judge that their loss of favor isn’t entirely undeserved; one might argue that ‘An Homily for repairing and keeping clean, and comely adorning of Churches,’ however worthy its subject, need not have confessional status.

But my goal here is not to defend the Homilies in their entirety (although even said sermon about the adorning of churches has things to say for it!). Even as eloquent a defender of the contemporary value of the Homilies as Gerald Bray admits that some of the Homilies “seem quaint and far removed from modern concerns,” although I agree with him that the doctrinal homilies in particular are excellent. The Homily on Scripture (probably by Cranmer; the first homily of the first Book) and the trilogy of homilies by Cranmer on salvation, faith, and good works (Homilies 3-5 of the first Book) are especially good, and the editors of the justly celebrated 1662 Book of Common Prayer: International Edition have done well to include the homily on salvation as an appendix in that prayer book.

But I’m getting off topic. Today, Holy Saturday 2023, especially if you are looking for devotional reading now and in Eastertide, I want to direct your attention to two homilies of the second Book, the one for Good Friday and the one for Easter-Day. These two were from the lay theologian and preacher Richard Tavener’s 1540 Epistles and Gospelles with a Brief Postyl upon the Same.2 They are two of five of the Second Book of Homilies specifically organized around the church year; they join homilies for Christmas, Pentecost, and Rogation Week.

Most of all, I’d encourage you to read them. Unfortunately, they are somewhat difficult to find online - evidence in itself of the Homilies’ relative obscurity. You can find the Good Friday Homily, split into two parts (as later editions generally did) at North American Anglican here and here. I suspect they’ve taken the text from a 19th c printing, so spelling conforms to modern rather than 16th c. usage. For some reason, they don’t have the Easter homily there, but you can find it here at the Anglican Library, albeit with 16th c. orthography. Alternatively, you can find fine digitized versions of the Two Books of Homilies on Google Books, such as here.

Here are a few reflections that might (I hope) whet your appetite to turn to the sources themselves:

If you find yourself looking for a sermon that clearly preaches the cross and Christ crucified, the Good Friday Homily does it in spades. I’m reminded of Fleming Rutledge’s adage that the crucifixion is appropriate because “the hideousness of the death corresponds to the dreadful, annihilating Power and malevolence of Sin”: the Homily sets forth both the horrific evil of sin and the grace of God unapologetically as joined in a mysterious, awful way on the cross. The goal of the sermon is to elicit hatred of sin and thanksgiving to Christ for his redeeming sacrifice, the benefits of which are applied to us by faith alone. This hatred and thanksgiving alike then lead to a transformed life of loving one’s neighbors and forgiving those who have wronged you, not as a means of earning salvation (the Homily is staunchly Protestant on this point!) but as the fitting response to what Christ endured for each one of us.

I found a portion of the second part of the Homily, in which the author enjoins the listeners to imagine Christ crucified before them,3 particularly arresting, so I will quote it at length:

Call to mind, O sinful creature, and set before thine eyes Christ crucified. Think thou seest his body stretched out in length upon the cross, his head crowned with sharp thorns, and his hands and his feet pierced with nails, his heart opened with a long spear, his flesh rent and torn with whips, his brows sweating water and blood. Think thou hearest him now crying in an intolerable agony to his Father, and saying, My God, my God, why has thou forsaken me? Couldst thou behold this woful sight, or hear this mournful voice, without tears, considering that he suffered all this, not for any desert of his own, but only for the grievousness of they sins? O that mankind should put the everlasting Son of God to such pains! O that we should be the occasion of his death, and the only cause of his condemnation! May we not justly cry, Woe worth the time that ever we sinned? O my brethren, let this image of Christ crucified be always printed in our hearts; let it stir us up to the hatred of sin, and provoke our minds to the earnest love of Almighty God.

The Resurrection homily does not quite reach the emotional heights of the Good Friday one, but it too is very much worth your time. It gorgeously preaches the resurrection, “that great and most comfortable article of our Christian religion”, “the very lock and key of all our Christian religion and faith.” If the Good Friday homily focuses on themes of substitution and sacrifice, here we see themes of victory and death’s conquest brought to the fore. Note, though that this does not identify ‘victory’ solely with resurrection. Tavener is too good a theologian for this; rather, the resurrection proclaims the victory won on the cross. The victory was “by the power of his death” and then “openly proved…by his most victorious and valiant resurrection.” This Easter sermon is still a proclamation of the cross, but from the vantage point of Easter, where it is revealed clearly for all to see that the cross was no defeat but a great victory of death, hell, and the devil. And in response to this glorious victory shown forth on Easter Day, it is the Christian’s responsibility to “in the rest of our life declare our faith that we have in this most fruitful article…in rising daily from sin to righteousness and holiness of life.” Thus the sermon concludes with moral exhortation, as a life sanctified by the power of the Holy Spirit is the most proper way to keep the Easter feast.

I could write more, but as I said, I mostly hope to encourage you to go to the texts themselves. Dearly beloved in the Lord, I wish you a joyous celebration of Easter. May you be filled with the Spirit of the risen Christ and rejoice in his great victory which he won for us on the cross and displayed in the glory of his Resurrection.

Indeed, the confessional status of Wesley’s Standard Sermons for Methodism owes a great deal to the example, if not in all respects the specific content, of the Homilies - the Anglicans and the Methodists are the two Christian bodies which have adopted homilies as part of their confessional heritage.

Incidentally, this makes these the only Homilies, indeed the only part of Anglican Formularies as a whole, known to be written entirely by a layperson - although of course Elizabeth I’s editorial hand is significant in the Articles and Homilies alike.

Here Tavener is drawing upon a pre-Reformation style of pious use of the imagination associated in particular with the Brethren of the Common Life. I’m thankful to Dr Matthew Shadle for this insight.