My wife Sarah and I are currently staying with a friend in the north of England, and we recently took a quick trip to the Lake District. It was, needless to say, absolutely stunning. Along with some walks and taking in the gorgeous scenery, we naturally attempted to enter every church we came across. At St. Martin’s, Windermere we came across an interior decorating scheme that I had never seen before and wanted to share with you.

The current church building there dates from 1483; an earlier church on that site burned down in 1480. There was substantial renovation in 1870, when meant, alas, the removal of the triple-decker pulpit (cue requisite grumble about the Victorians).

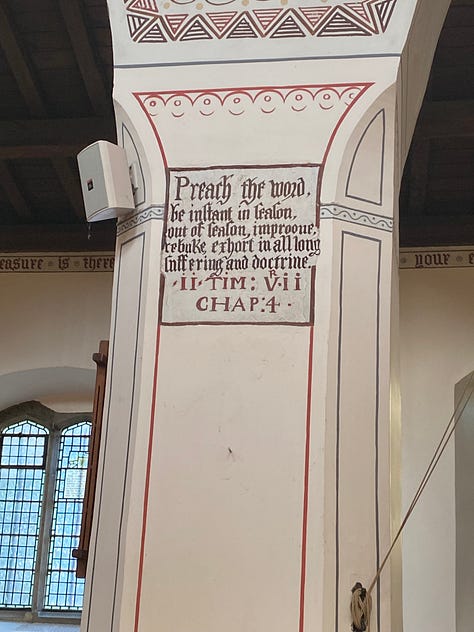

Something I found particularly interesting about the decorative scheme was the use of a good deal of text. There was the requisite Decalogue, Creed, and Lord’s Prayer on the (nineteenth century) marble reredos behind the Communion table. The crossbeams in the nave and some of the spandrels1 included various Scripture passages. I am very fond of such use of Scripture; I have seen them fairly often in Reformed churches in Switzerland but less commonly in England. I would not be surprised if these were once much more common in English churches, but defer to those who know more about such things than I!

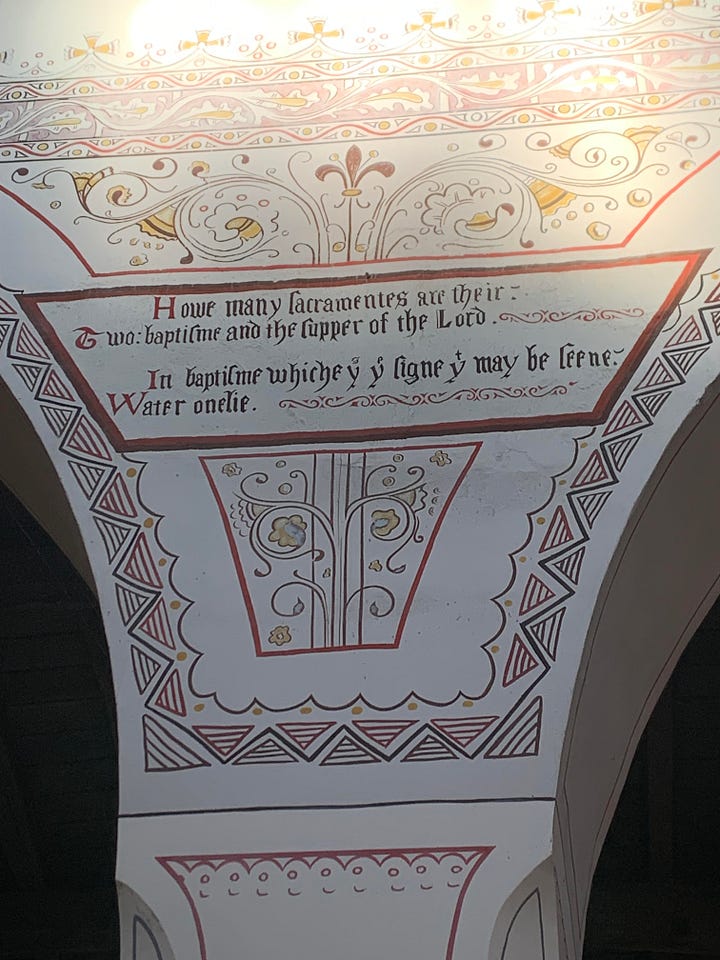

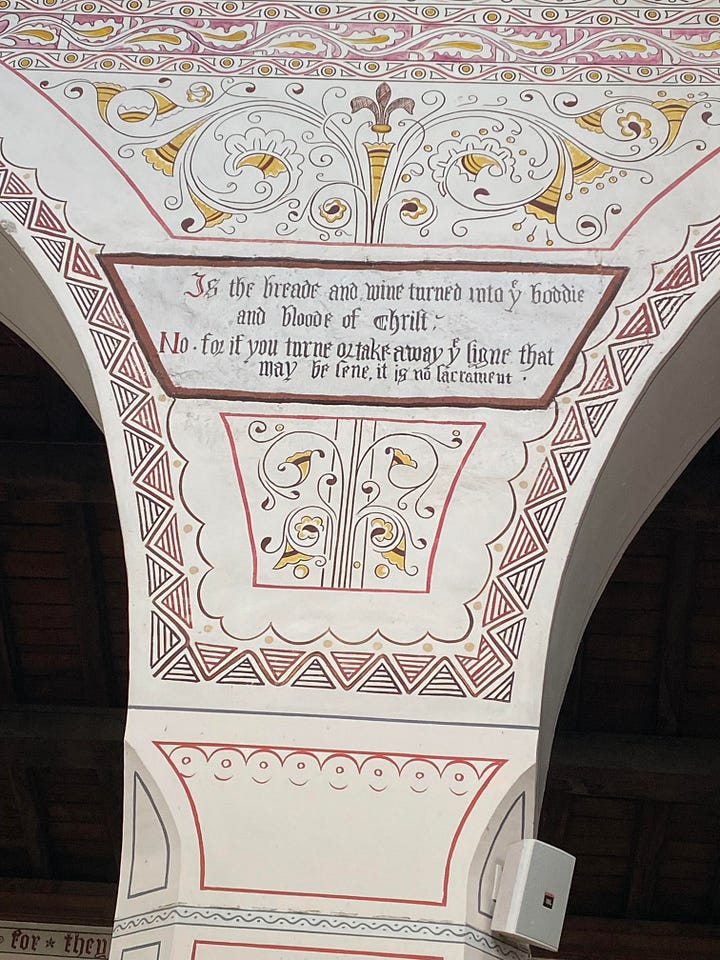

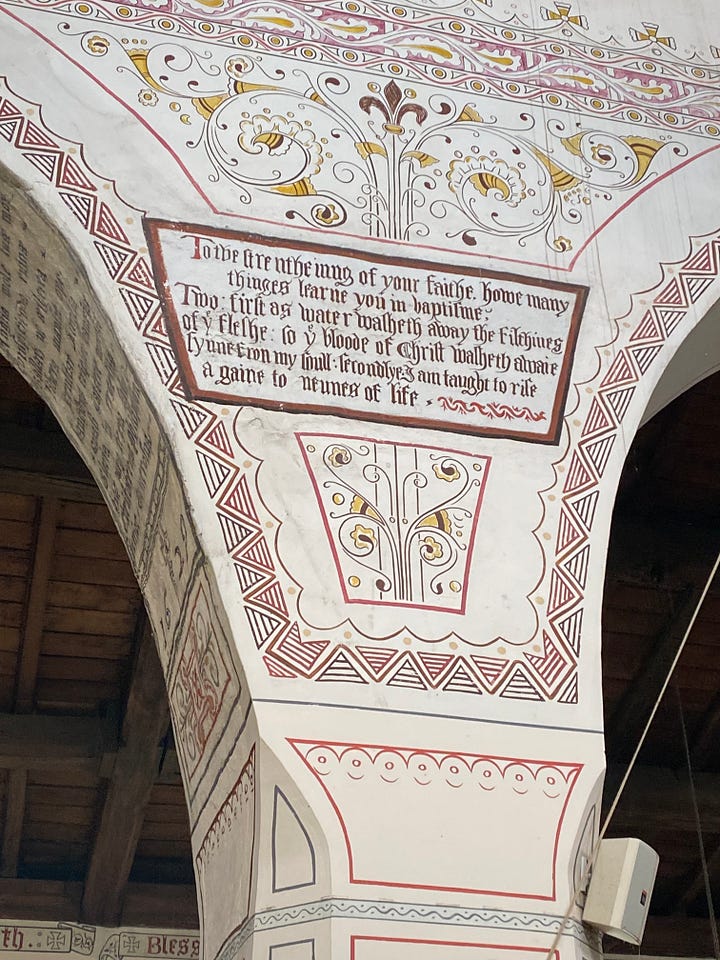

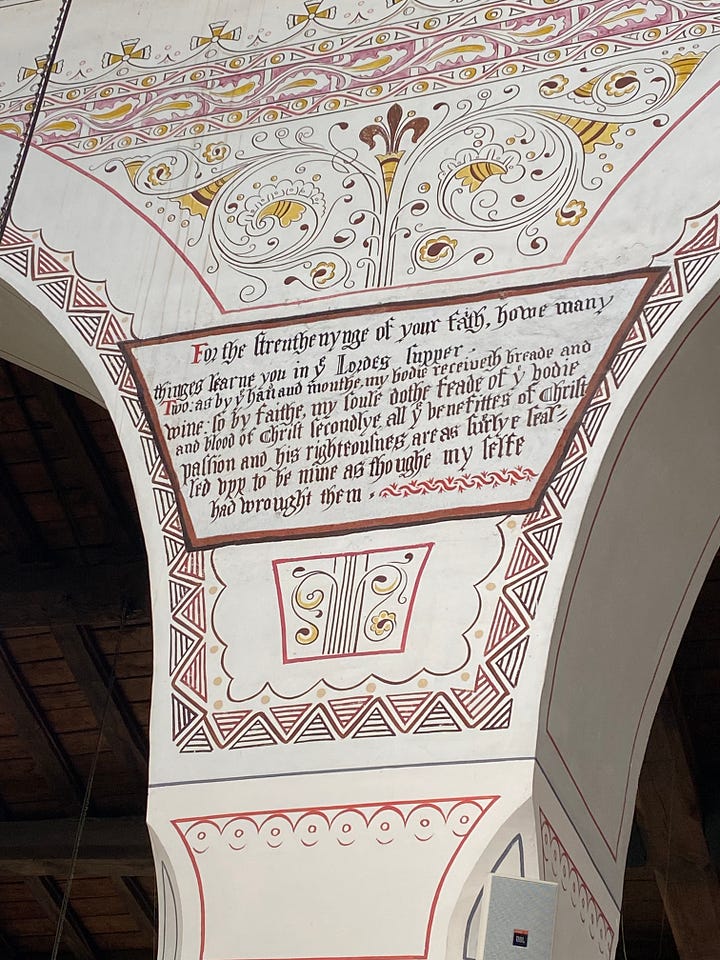

What I found particularly interesting, though, was the use not only of Scripture passages but also of catechetical texts in the church’s decorating scheme. The spandrels in the nave facing the middle of the church are inscribed with the several catechism questions and answers about Baptism and the Lord’s Supper. I took pictures of some of them:

I’ve transcribed them here, from left to right. Note that I’ve preserved the original spelling.

On the number of sacraments:

How many Sacraments are their?

Two: baptisme and the supper of the Lord.

Against transubstantiation:

Is the breade and wine turned into the boddie and bloode of Christ?

No. for if you turne or take away the signe that may be sene, it is no sacrament.

The benefits of baptism:

To the strentheinng of your faithe, howe many thinges learne you in baptisme?

Two: first as water washeth away the filthines of the fleshe: so the bloode of Christ washeth awaie synne from my soull: secondlye, I am taught to rise againe to newnes of life.

The benefits of the Lord’s Supper:

For the strenthenynge of your faith, howe many thinges learne you in the Lordes Supper?

Two: as by the hand and mouthe, my bodie receiveth breade and wine: so by faithe, my soule dothe feade of the bodie and blood of Christ secondlye, all the benefittes of Christ passion and his righteousnes, are as surelye sealled upp to be mine as thoughe my selfe had wrought them.

I did a little digging, and these are from the catechism Short questions and answeares, conteining the summe of Christian religion. This text was first published in 1579 and went through some 35 editions in three different versions in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It is often attributed to Robert Openshaw, but Ian Green argues in his landmark work on English catechisms that it should in its original version be ascribed to Eusebius Paget instead. Openshaw produced an expanded version with Scripture references. The parish’s historical leaflet says that these spandrel inscriptions likely date to around 1600. To give the Victorians their due, they were rediscovered and repainted at the 1870 renovation, having previously been painted over.2

There’s a lot that could be said about this. First, a question to my readers: do any of you happen to know of any other English churches that use catechism texts in this way? It’s the first time I’ve encountered it, and I’m curious about how unusual it is.

Second, it reminds us of the diversity of catechetical material in early modern England (a point that Ian Green has made very clearly). There were a lot of catechisms in very regular use beyond the prayer book catechism (which didn’t receive a section on the sacraments until 1604) and Alexander Nowell’s. I wonder if the fact that Nowell’s is still somewhat well known today owes more to its inclusion in the Parker Society library than its sixteenth century status. His catechisms were popular but not dramatically more so than other sixteenth or seventeenth century entries in the genre, and there were some that went through significantly more editions than his.

Third, we get a nice reminder of the broadly Reformed nature of Church of England sacramental teaching. To be fair, the images above don’t explicitly rule out a Lutheran account (although the catechism as a whole very clearly does, and I don’t remember which other questions and answers were painted on the spandrels - alas!). But as I’ve noted before, the analogy between the physical sign and invisible grace is a classic element of Reformed sacramental thought.

Finally — and perhaps of broadest interest beyond Reformation historians — I think it’s worth thinking a little about the experience of worship in this church. Imagine going to or from the communion table and glancing up at the spandrel to remind yourself of what the Supper is and how it benefits you, or of letting your eyes wander during a less-than-scintillating sermon and meeting Scripture and catechism. I think it’s really quite lovely.

The spaces above a column between two arches

I’ll note here that I haven’t found a printing that matches word-for-word the spandrel texts, but this is not a surprise, as small variations between editions were not unusual and there were a number of editions printed between 1589 and 1600 that we don’t have an electronic copy of — regardless, it clearly is this text.

I should add re: my comment that I rarely see Scripture used in decorative schemes in English churches that obviously once Commandment boards were required. It's Scripture verses painted on the walls or columns, as in this church, that I have seen less often.

This is *really* interesting to see and almost providential as I've been thinking about using more text based graphics for church art in a way that's rooted in the Reformed tradition - especially important as I want to avoid appropriating aesthetics from Islamic art.

Like you, I'm used to seeing the Commandment boards and also scripture interspersed with illustrations (late Victorian/Edwardian anglo-catholic circles), but this certainly expands the visual traditions to learn from, so to speak!