Anglicanism: A Love Letter

A while ago, a friend on Twitter asked me a question that has stuck with me: why do I want people to become Anglicans? After all, I emphatically do not think that Anglicanism is the one true church. And I reject the notion that Anglicanism uniquely occupies a via media position between Protestantism and Rome, arguing instead that it is one of a family of magisterial Protestant churches. So why Anglicanism, rather than Lutheranism or Presbyterianism – or for that matter any other part of the church Catholic?

It's a good question. And frankly, I care a lot more that people become Christians, and find churches that nourish them in a life of discipleship, than that they become Anglicans specifically. What matters to me, as the Articles of Religion say, is that inquirers find a church where the pure Word of God is preached and the sacraments are duly administered. I don’t think that Anglicans have a monopoly on this. And while I wish I could say that people can reliably find this in our congregations, I’ve also spent enough time in both the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Church of Canada to know that this is not always the case. I would much rather people be in a Gospel-centered magisterial Protestant church of any stripe – or for that matter a Roman Catholic, Orthodox, or Baptist one – than in a wishy-washy Anglican one. I don’t mean to deny the importance of denominational differences, and I do have substantial disagreements especially with those latter three traditions. But the differences we have are, I believe, second order ones. The confession of Jesus’ divinity, of our need for salvation, of salvation wrought through Christ’s cross and resurrection, of the second coming – all this is more basic, more important than even very important disagreements about sacraments or church order or how it is that Jesus saves. Even though these latter disagreements may rightly prevent the establishment of visible unity among separated churches until they are resolved, we can and should recognize each other as parts of the one true Church of Christ. And for my part I would much rather people go where they are fed, where they can grow in Christ, than stick around in a spiritually-adrift congregation of a denomination that looks great on paper.

And yet I do think that, if you are looking for a church and there is a faithful Anglican option around, there are good reasons to consider becoming Anglican rather than going to the nondenominational congregation or the other magisterial Protestant church or the Roman Catholic parish down the road. There are, I believe, particular charisms that Anglicanism has even among its fellow magisterial Protestant churches, particular strengths that have drawn me to the tradition and lead me to commend it to others. And indeed, I think that there are gifts that Anglicanism can offer the broader church catholic, regardless of whether a given individual chooses to join our fellowship within the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. And so – especially on a Substack which tends to be preoccupied with the problems with the tradition within which I find myself – I want to offer, as it were, a love letter to Anglicanism, an attempt to answer my friend’s question.

Why Anglicanism? I think that Anglicanism at its best offers a robust tradition of Protestant irenicism, a sound ascetical theology for clergy and laypeople alike, and a commitment to the maintenance of catholic order and heritage along with Gospel preaching.

Anglicanism’s Irenicism

One particular strength of the Anglican tradition is a history of generous irenicism towards other Christian bodies, a willingness to see itself as simply a part of the larger church rather than staking an exclusive identity-claim as the one true church. Indeed, my statement above that I care a lot more that people find a faithful Christian church of whatever tradition than that they find an Anglican one is rooted very specifically in the Anglican tradition. My dissertation focuses on how Elizabethan Anglicans understood their relationship to other Christian churches, and especially Protestant churches on the Continent, and I argue that this sort of irenicism is baked into Anglicanism from the beginning.

Richard Hooker, of course, is the example par excellence: he enraged his disciplinarian opponents by arguing that the Roman Catholic Church remained part of Christ’s Church (although of course he was less willing to see people remain within it than I); he also sought to manage differences between Reformed and Lutheran Protestants without mutual anathematization. This irenicism did not mean a refusal to stake a stand on disputed issues; Hooker is clearly a Protestant rather than a Roman Catholic, and indeed a Reformed Protestant, taking the Reformed side on the major eucharistic and Christological questions dividing Lutherans from Reformed. Yet he married these commitments to a commitment to generosity towards other Christians in a way that I think is laudatory – and particularly Anglican! Indeed, even in his frustration with his ‘Puritan’ adversaries, he sought very explicitly to make the Lawes an irenic book, arguing with his opponents that their shared commitment to the Protestant Gospel was expressed well in the current church order and liturgy of the Church of England.

This irenicism, not only a good in itself, also enables Anglicans to benefit profoundly from the those outside our confessional boundaries, narrowly construed. We can read not only our own divines but Luther and Calvin and all the rest. There is a danger here, of the neglect of specifically Anglican sources and thinkers, of the abandonment of the Articles, Prayerbook, and Ordinal as norms for our theological and liturgical life, of an irenicism turned to a mushy lowest-common-denominator ecumenism. And yet it is a danger worth facing, it seems to me, for it is such a blessing to be able to learn to love God and neighbor better from Christians of all sorts.

Now, a few necessary caveats: it’s not that Anglicans alone are capable of this irenicism. Article XIX, the account of the church that I quoted above to justify a generous ecclesiology, is derived from the Lutheran Augsburg Confession Article VII. Richard Hooker stands in a tradition of early Reformed generosity across Reformed-Lutheran lines. And indeed much contemporary ecumenism takes the line sketched out above, that all participants in ecumenical dialogues are genuine Christians, that salvation is possible in all sorts of Christian churches, and so on. Moreover, it must also be admitted that we Anglicans do not always express the irenicism I am claiming as particularly Anglican. Whether one thinks of the fierce anti-Catholicism in our past, or – much more common now, at least in North America – post-Oxford-Movement scorn towards ‘Protestants’, Anglicans too often neglect this part of our heritage.

And yet I do think that we can claim our long history of irenicism as an Anglican distinctive, and that our traditional combination of irenicism with a willingness to take confessional stands might be worth retrieving today beyond Anglicanism specifically. Hooker and the Articles alike point us to an alternative between the unsatisfactory choices of mushy lowest-common-denominator ecumenism and vituperative, hostile confessionalism. This, it seems to me, is a good reason to become an Anglican.

The Daily Office and Anglicanism’s Ascetic Theology

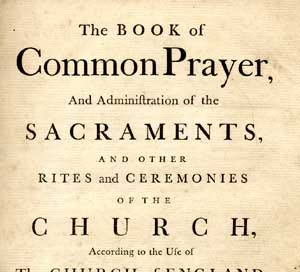

Another particular strength of the Anglican tradition is the pattern of worship set forth in the Book of Common Prayer, the way that the Anglicanism invites all its people – clergy and lay alike – into regular psalmody, Scripture reading, and prayer, cycles of feast and fast, commemoration of the mighty acts of our salvation. Of course, Anglicans are far from the only Christians who observe the liturgical calendar or have an ordered liturgical life. But I do think that the centrality of the daily office for all Christians is a historic distinctive of Anglicanism. I’ve written at length on the office before – you can read my reflections here – so I will be somewhat brief.

In short, Thomas Cranmer brilliantly reformed the incredibly complex daily office of pre-Reformation England, producing two services of daily prayer organized around extended psalmody, Scripture reading, and prayer. Morning and Evening Prayer were to be said by every minister, and every incumbent was to arrange for it to be said publicly every day in every parish church. Laypeople were to be encouraged to attend, and a genre of devotional literature encouraged them to say the daily office by themselves even when they could not make it to the parish church to attend corporate daily worship. In so doing, Cranmer sought to return a tradition of daily prayer which had become heavily clericalized and monasticized to the people, inviting all Christians into the church’s daily round of prayer for God’s glory and their own edification, their growth in the knowledge and love of God.

And one need not posit a golden age in which every priest said his (they were all men back then, of course) office and every parish church was full of worshippers every morning and evening to recognize that this focus on the office is a particular mark of Anglicanism. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches, liturgical daily prayer remained largely the preserve of priests and monks (Roman Catholic laypeople were only invited to join in liturgical daily prayer by themselves by Vatican II!). Public services of the church’s daily prayer are rare, especially in the Roman Catholic Church (the Orthodox at least often have public services Saturday night and Sunday). Other Protestant churches, then, either jettisoned set daily prayer at the Reformation or saw daily prayer orders gradually fall into disuse. In a unique way, Anglicanism has retained the daily office as a form of regular worship of God and sanctification of Christians for all Christians, not just for priests. Even today, it is not unusual for Anglican churches to offer at least some regular public celebration of the daily office, and the office’s inclusion in Anglican liturgical books means that laypeople who own these books at least have access to the office, whether or not they actually pray it. It is not that only Anglicans have a tradition of daily liturgical prayer, or that Anglicans always faithfully follow this tradition. But the emphasis on the office for all is, I am convinced, an Anglican distinctive.

Moreover, this emphasis has shaped Anglican theologies of worship and of asceticism or discipleship in helpful ways. The office as an act of worship reminds us that worship is not about emotional highs, indeed not grounded in a particular affective experience at all, but about the faithful offering of our time and attention to God in prayer (this is not to say that affections set aflame by God don’t matter in the Christian life, of course – but simply that they are not the substance of Christian worship). Similarly, then, the Christian life of discipleship is characterized above all by faithful, regular, disciplined attention to the Word: the office is a means of having God’s Word always in front of you, to give you opportunities to ruminate in it, to luxuriate in it, even as you offer prayer and praise to almighty God. I do not mean to suggest that spontaneity, individual devotion, the movement of the Spirit outside of set liturgies and times have no place in the Christian life – far from it! But rather that these are best anchored in the church’s regular rhythm of prayer, not just on Sundays but on every day of the week.

And Anglicanism invites you – yes you! – into exactly this rhythm of prayer, not reserving it for the clergy but offering it to all Christians. This, too, strikes me as a very good reason to become an Anglican.

Anglicanism as Light-Touch Reformation

A third reason that I love Anglicanism is that at its best, it combines a clear exposition of the Gospel with a reverence for the Christian past, a refusal to prune more from our inheritance than is necessary to clearly set forth salvation by grace alone, apprehended through faith alone. By a combination of intention and the accidents of history, the Anglican Reformation has been a ‘light touch’ one.

This is about as close as I will come to the ‘via media’, so it is worth emphasizing that this is in no way a denial of Anglicanism’s Protestant character. No: I love how fulsomely Anglicanism sets forth the Gospel! In its Articles, its Homilies, its Prayerbook – as J.I. Packer has noted, BCP Holy Communion is organized around cycles of guilt, grace, and gratitude – Anglicanism proclaims justification by faith alone. Thanks be to God! Yet while embracing this specifically Protestant understanding of the Gospel, Anglicans have nonetheless maintained continuity with the pre-Reformation past to the greatest extent possible. The retention of a reformed daily office, as discussed above, is a good example of this tendency. So too is Cranmer’s careful liturgical work framing the Book of Common Prayer more broadly, and the high view of the sacraments of Baptism and Holy Communion evident in that book. Similarly, the retention of episcopacy: while I reject the view that churches that are not episcopally-ordered are not true churches or that the monarchical episcopate is required by Scripture, fidelity to the long-standing tradition of the church strikes me as a reason to keep bishops when possible. There is a reason, too, that Anglicans have long been known for patristic studies; this even survived to my seminary curriculum, where patristics was expected of Anglican students (but not of our confreres in other magisterial churches). And indeed, the restoration of monasticism in Anglicanism strikes me as a healthy development, even as I think there were good reasons for sixteenth century Protestant skepticism of what the institution had become in late medieval piety. One thinks again of Richard Hooker here (he is rarely far from my mind!): when he outlines in Book V of the Lawes the criteria upon which decisions should be made about whether a given element of the church’s external life is ‘convenient,’ one of the criteria is conformity to the “antiquitie, custom, and consent” of the church when possible.

Now I hasten to add that once again Anglicans are not the only tradition who can lay claim to the combination of the Gospel and a (reformed) catholic order. I wouldn’t dare suggest that the Gospel is absent from the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches, for one, even as their understanding of it is somewhat different from us Protestants. And on the Protestant side of things, every point in Anglicanism’s favor I mentioned above can also be found in other Protestant churches. Lutherans and the Reformed alike have great reverence for the sacraments and rich sacramental theologies. Some Lutheran and some non-Anglican Reformed churches retained the episcopate. The sixteenth century Reformers and the great Protestant systematizers of the centuries following were steeped in patristic thought, whatever their particular confession. There are Lutheran, and even a handful of Reformed, monastics. The Lutherans in particular may well contest Anglicanism’s claim to be the most conservative Reformation, cautiously discarding only what is necessary to be discarded.

But for a variety of reasons, over the development of the Protestant traditions through history, Anglicanism in general strikes me as best combining a commitment to the Gospel with a generous relationship to – even reverence for – the Christian past (if anything, our danger is letting our reverence for the past eclipse our forthright proclamation of the Gospel and lead us to a rejection of our specifically Anglican heritage, but that’s another matter). And this too strikes me as a good reason to become an Anglican.

And so this, ultimately, is my attempt at an answer to my friend’s question: Anglicanism’s Protestant irenicism, its liturgical and ascetic life (especially the daily office), its combination of evangelical faith and catholic order strike me as some of the best reasons for a magisterial Protestant looking for a church to become Anglican rather than some other sort of Christian. You might add others. I have up to this point avoided aesthetic argument, but I do believe that our traditional liturgies are the most beautiful in the English language, that Anglican choir dress is the most dignified and lovely clerical vesture, that our musical tradition is a jewel (more in daily office settings and psalmody than hymns; our hymnody owes a great deal to Lutherans and Nonconformists). Now, I do not write this to urge you away from the church where you currently are; if you are in a place where you are nourished upon the riches of God’s grace, thanks be to God! But if you do find yourself looking for a church, I would encourage you to give the Anglican church down the road a visit (or contact me and I’ll try to sort out a church recommendation!). And regardless of the particular ecclesial community within the one Church of Christ in which you find yourself, I hope that you might receive some of Anglicanism’s particular strengths as gifts to you, even as we Anglicans seek to learn from and draw closer to God through the charisms of other churches. There is, after all, ultimately one church and one shepherd – one Lord, one faith, one baptism – one hope of glory to which we are all called.

I've just got round to reading this. Just wonderful! And very nuanced and considered, particularly in places where descriptions of our tradition can so often tend to oversimplify, rely on myth, or otherwise err.

And in a context where Anglicanism can be far too often improperly described as a "big tent" or something which lacks distinctives, it's wonderful to read something which so clearly highlights and embraces those distinctives, and that makes clearly the case for being an Anglican Christian.

This is a compelling read, and if more American Anglicans sounded like you I might have landed in the Anglican church 20 years ago.