Why Anglican Clergy (And Everyone) Should Pray the Office

Towards a theology of the daily office

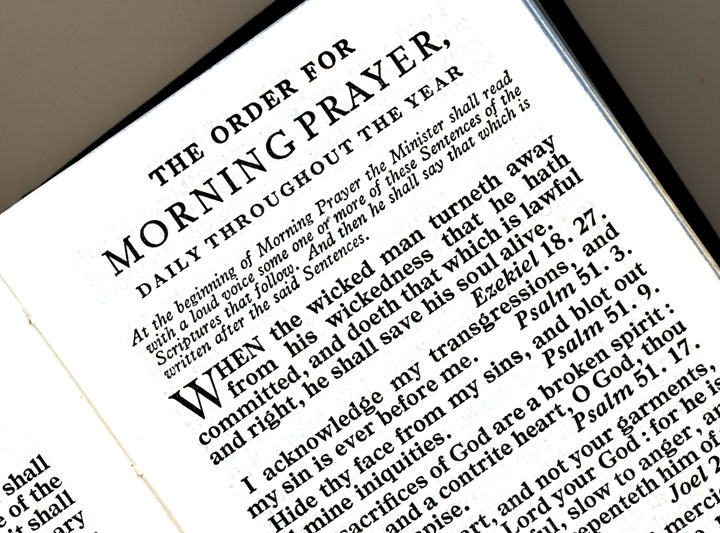

And all Priests and Deacons are to say daily the Morning and Evening Prayer either privately or openly, not being let by sickness, or some other urgent cause.

And the Curate that ministereth in every Parish-Church or Chapel, being at home, and not being otherwise reasonably hindered, shall say the same in the Parish-Church or Chapel where he ministereth, and shall cause a Bell to be tolled thereunto a convenient time before he begin, that the people may come to hear God’s Word, and to pray with him.

- Concerning the Service of the Church, Book of Common Prayer 1662.

The daily office – that is, the church’s daily round of liturgical prayer, oriented in particular around morning and evening prayer – has a rather ambiguous place in the life of my own Episcopal Church at present, and, I gather, Anglicanism more broadly. On one hand, the 1979 Book of Common Prayer describes “The Holy Eucharist, the principal act of Christian worship on the Lord’s Day and other major Feasts, and Daily Morning and Evening Prayer, as set forth in this Book” as “the regular services appointed for public worship in this Church” (BCP, p. 13). While the Eucharist is clearly given pride of place, the daily office is nonetheless treated as part of the public worship of the church. The very names of the two main services of the Anglican daily office, Daily Morning Prayer and Daily Evening Prayer, suggest that they be said, well, daily. And yet, outside of monasteries, seminaries, and a few cathedrals and Anglo-Catholic parishes, the daily public celebration of morning and evening prayer is vanishingly rare in the Episcopal Church. There is a lack of good survey data on the spiritual practices of Episcopal clergy, but in conversations with priests I’ve had, Twitter polling, and the like, it seems clear that few priests and deacons say morning and evening prayer daily, and many do not engage with the office at all.

This, I believe, should not be. Clergy – everyone, really, but certainly clergy – should pray morning and evening prayer daily, publicly if at all possible, and churches should arrange clergy work schedules and expectations to better facilitate this. Both for clergy who find themselves committed to a Protestant Anglicanism and those aligned more closely with Anglo-Catholicism, there is abundant precedent in specifically Anglican history and in the broader Catholic inheritance for such a practice. But of course, the mere warrant of tradition, be it the rubrics of the old prayerbook for the Protestants or the decrees of Vatican II for a certain sort of Anglo-Catholic, will likely not prove sufficient to convince in the contemporary Episcopal Church, for better or worse. To understand the logic behind this expectation, we need to consider the office’s meaning, firstly as an objective act of worship and secondly in its subjective dimension as an aid to growth in piety, holiness, and sound doctrine.

The argument from tradition is clear enough. While the early development of the office, the relationship between ‘cathedral’ and ‘monastic’ uses, the various ways it has been celebrated are of great interest to the liturgical historian, for us the point is simple. About as far back as we can tell, clergy were expected to offer worship to God at set daily times, worship which consisted of psalmody, Scripture, and prayers of intercession and thanksgiving. This was true for the Church in England at the time of the Reformation; this was reaffirmed in Roman Catholicism when the breviary was reformed after the Council of Trent; it was reaffirmed again at the Second Vatican Council. For us Anglicans, then, from the 1552 Book of Common Prayer on to the 1662, there has been a rubric like the one quoted at the beginning of this piece, binding all clergy to the celebration of morning and evening prayer, and to be arranged to be said publicly by those with pastoral charge of a parish, with the congregation invited to participate, if at all possible. For those Anglicans who are in churches that remain committed canonically to the doctrine and liturgy of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, it seems to me that this rubric remains binding (although I confess to being no canonist). Here in my own Episcopal Church, however, the rubric disappeared from our 1789 Book of Common Prayer and has not made a reappearance. So there is no question, for Episcopalian clergy, of a canonical or rubrical obligation to pray the daily office - although it is perhaps worth noting here, as my friend Tony Hunt likes to point out, that the office fundamentally consists of Scripture reading and prayers, which Episcopal clergy do do vow to be faithful in. All the same, an argument drawing upon the Anglican or Catholic precedent must be, for Episcopalians, an argument from tradition or custom. This may be compelling to some, but I imagine that for most, more persuasion is needed than “this is how they did it in the 15th, or the 18th century,” or “this is how our Roman Catholic siblings do it.” Fair enough. Besides this history, why might one choose to pray the daily office?

To answer this question, it is important first to address the question of what the office is. A lot of the confusion around why might pray the office stems from a misunderstanding on this front. The office is not a private devotional practice which happens to be bound in a book with the various public liturgies of the church, which an individual may find more or less edifying. This is not to deny, of course, that the office might bear spiritual fruit in us over time. But it is to say that, as the rubric in the 1979 BCP quoted above makes clear, the office is in fact part of “public worship in this Church.” The office, even when the priest prays it alone, is a liturgical act done as and on behalf of the Church, as part of the worship that the Church offers to almighty God. It is striking that many of the Anglican prayer book commentaries (Sparrow, Mant, Overall) analogize the office to the daily morning and evening sacrifice of ancient Israel. Thus Bishop Sparrow writes that in the Mosaic Law, God instructed the Church of Christ that “besides the daily private devotions of every pious soul, and the more solemn sacrifices upon the three great feasts of the year; Almighty God requires a daily public worship, a continual burnt offering, every day, morning and evening.” This commandment, Sparrow believes, is not abrogated for the Christian; “Morning and evening, to be sure, God expects from us as well as from the Jews, a public worship.” Now, as a historical matter, it is unlikely that Christian daily prayer descended in any straightforward way from Jewish temple sacrifices. But this does not mean the analogy is without value. To make a perhaps obvious point, the daily sacrifice in the temple were not primarily about, as far as we can figure, fostering particular spiritual experiences in the worshippers; not finding it fruitful was no reason to omit the obligation to sacrifice. For the temple sacrifices – and thus too the daily office – were primarily concerned not with the spiritual benefit to the sacrificers but rather with the worship of God.

Sacrosanctum Concilium, the apostolic constitution of Vatican II dealing with liturgy, understands the daily office as a mode of the Church’s participation in Christ’s priestly intercession for us before the Father. One could do much worse for a theology of the office: in our imitative participation in the priesthood of Christ our head, the Church offers up praise, thanksgiving, and intercession to the Father in the power of the Spirit (I hasten to add, here, that while it is understood rather differently, the notion that we participate in Christ’s priestly office has a venerable Reformed, and not only Roman Catholic, pedigree!). It is not, of course, that the particular form that Anglicans use for the office is explicitly God-ordained, but as Anglicans we believe that it is within the competence of the church to promulgate liturgies and demand adherence to them from the faithful. Ideally, this exercising of our common Christian priesthood by a twice-daily sacrifice of praise would be the action of all the people of God. Thus the rubrics from the 1662 at the head of this piece call for the daily office to be celebrated publicly and a bell rung to call the people to prayer. Indeed, it seems to me that a truly Christian polity would make it possible for the faithful to attend the daily public celebration of the offices, but that is a matter for another time. While any Anglican can (thanks be to God!) pick up a BCP and join in the public prayer of the Church, they may also be said to act, in a very particular way, vicariously through their clergy. Clergy cannot do private devotions on their congregation’s behalf, nor can they receive the Lord’s Supper on their congregation’s behalf. One cannot have a wholly vicarious relationship with God! But clergy might be rightly said to be set aside by congregations to engage in the public prayer of the Church on their behalf. Clergy pray the office for themselves, but also as representatives of the congregation, engaging in the public prayer of the Church. Understood this way, it doesn’t particularly matter if the office is a devotion that ‘resonates with’ the clergyperson. Certainly one would hope it at least occasionally does – more on that anon – but at core, clergy pray the office not as a private devotional enterprise but as those set aside by the congregations to pray the liturgy (which, after all, originally meant a ‘public work’ or ‘work on behalf of the people.’) for them and for the world.

However, the good news is that the office, over time, does have real spiritual benefits for those who pray it, laity and clergy alike. The Anglican office in particular was reformed by Cranmer to be absolutely steeped in Scripture. Both morning and evening prayer are characterized in their ‘classical’ 1662 form by lengthy psalmody, two substantial lessons from Scripture (typically a chapter) followed by canticles, and then prayers. While this format has been adjusted over the years, especially since the Liturgical Movement, typically with an eye towards increasing variety and shortening the lessons, the Anglican office remains deeply Scriptural. To pray the office is to hear, over and over again, God’s Word, to ‘read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest it’ for, as Cranmer writes, “a great advancement of godliness.” In “Concerning the Service of the Church,” Cranmer discusses the benefits of the office for ministers and for laity. For the ministers in particular, this prayerful exposure to Scripture should make them “stirred up to godliness themselves, and be more able to exhort others by wholesome doctrine, and to confute them that were adversaries to the truth.” The people, moreover, who come to pray the office along with their clergy will “profit more and more in the knowledge of God, and be the more inflamed with the love of his true Religion.” This ordered, prayerful exposure to Scripture is ordained not simply as an objective act of worship towards God (although it is that!) but for our own great gain. It is not designed to be the whole of anyone’s prayer life; I think that Martin Thornton’s threefold rule of the Lord’s Supper, the daily office, and private devotion is very sound. But it does, as it were, do things for the pray-er, who is not only joining herself to Christ’s priestly office in this twice-daily sacrifice of praise and prayer to God, but in so doing is immersing herself yet more fully in God’s Word.

Why should one pray the office, especially if one is a clergyperson? It is not only a matter of adherence to tradition, although here at least tradition both Anglican and broadly Catholic points us in the right direction. Rather, the office is the Church’s daily public worship of God, the Church’s participation in Christ’s priestly work as it praises God, gives thanks to him, and intercedes for itself and the world. All are welcome to – and indeed, ideally all would – participate in this prayer of the Church. But clergy are set aside to do what the demands of many people’s vocations do not allow, to offer like incense the Church’s prayer to God. Moreover, the Anglican form of this public worship is designed to have a particular spiritual benefit of immersing the person praying in God’s Word, increasing knowledge and love for the God who saves us. Now, there are of course many reasons that praying the office is difficult, especially for those balancing children or secular employment along with the exercise of ministry – although I must point out that our 1979 offices do not take a great deal of time. I cannot pretend to have a solution to every logistical challenge, or how to convince your vestry that it is part of your ‘job’ to spend twenty to thirty minutes at the beginning and close of each day in prayer. I can only say this: not only has the office borne tremendous spiritual fruit in my own life, but my conscience has persuaded me that it is my duty as a clergyman in Christ’s Church to pray it. I will all too often do it perfunctorily, sometimes I am sure it will simply be skipped (alas!), but I believe that my inevitable failures in my duty do not excuse me from the duty itself. And I hope and pray, dear reader, that you will join me as we exercise together the common Christian priesthood of joining in Christ’s constant intercession for us, giving voice to the silent praises of all creation in our praise and thanksgiving and intercession for us and for this world that God loves so much.

PREACH

Just got finished 🤗