Finally, brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is pleasing, whatever is commendable, if there is any excellence and if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things. – Philippians 4:8

I still have the copy of Luther’s Small Catechism that I was given for my confirmation class around twenty years ago. In the front cover I wrote in rather execrable middle-school handwriting the two principles that our pastor told us on the first day would govern the two-year confirmation course. Principle one: at the heart of every question is a Christian question. Principle two: the goal of confirmation is, in light of this fact, to teach us how to think as Christians.

These are, I think, two pretty good principles for thinking about Christian life and the goal of Christian formation, perhaps especially in the current moment. The affirmation that Christianity matters for how we conduct all aspects of our lives strikes me as a needful one. This is especially true in the face of real, and in some ways intensifying, culture pressure to compartmentalize religious commitment. Then, regarding the second principle, it’s necessary to defend the church’s authority to help us discern the Christian stakes of and act appropriately in the myriad decisions facing us.

I’ve been thinking lately about how to unearth and take seriously the Christian stakes of one of the characteristic experiences of contemporary life: our constant bombardment by and engagement with what rather depressingly gets called ‘content,’ how we interact with the massive amount of text, videos, and music with which we are constantly confronted. For I am increasingly convinced that, as my pastor told me all those years ago, at the heart of this question is a Christian question.

Now, I recognize that this suggestion that there are significant concerns for us as Christians around the media we consume might raise some hackles, especially from veterans of the more separatist forms of American evangelical culture of the last few decades. Many Christians believed (and still believe) that the potential power of the things they read, watch, or listen to was such that they had to spend all their time with treacly Christian knockoffs, that engaging with non-Christian culture was a sign of concerning worldliness, that following Jesus meant consigning themselves to moral and intellectual stultification.

I think that the prudential judgments that these evangelicals made were largely wrong, and their reliance on language of contamination or infection was signally unhelpful. But the basic principle is unimpeachable. Of course what we read, watch, listen to, sing, and so forth shapes us and how we view the world. And we cannot expect that it is shaping us in a manner compatible with Christian discipleship, given especially that much of it is governed by questions of profit rather than edification. Thus, it is worth paying attention to what media we are engaging with and how it may be shaping us.

After all, there’s a whole lot of material out in the world that is basically designed to take advantage of and intensify sinful desires: lust (most obviously – but not solely – pornography), anger (a good deal of algorithm-based social media), greed and covetousness (the entire advertising industry), hatred for the stranger (the media presence of many right-populists) and so forth. And so such material needs to either be rejected entirely (like porn) or, at the very least, engaged with carefully (like social media). One feels a bit like a square or a crank for saying so, but I think it’s indisputably true.

However, what I want to focus on is something even more basic and fundamental than the question of how to think about the merits (or lack thereof) of any particular piece of media. What I want to think about instead is the broader media environment we exist in, an environment dominated by capital’s attempts to seize our attention. And I want to ask what these ever-increasing attempts to capture our attention mean for Christian life.

To rehearse a rather commonplace, but I think absolutely correct, bit of social analysis, our contemporary moment is one in which the most powerful companies and most creative engineers have devoted themselves to capturing our attention in ever more individualized ways. Tech giants make their money by selling our attention to advertisers. To be successful, they have to maximize the amount of time and attention we spend on their platforms. And so they are incentivized to make their platforms as addictive as possible, to take deep-seated human desires for connection and recognition and use them to keep us scrolling, to constantly grab and re-grab our attention (because it is easier to grab attention anew than maintain it).

And so we have little pocket slot machines in the forms of smartphones with us at all times, with apps giving us perfectly calibrated quantities of dings and buzzes and bright notification icons to keep us coming back for more. Algorithms personalize our social media experience, especially on short-form video sites, so that we all-too-easily sink into a haze of endless scrolling of exactly what we want to see in that given moment. CEOs of AI companies boast that very soon their LLMs will be able to function as friends and lovers, replacing a need for human connection with endlessly agreeable, perfectly individualized pseudo-companions. All this is aimed at the goal of making money by seizing our attention.

We can all see the results. Nearly everyone I know complains that they can think less clearly, read and write less well, work uninterruptedly for shorter periods, and be less present in person with others because of the impact of our current attentional regime. As Chris Hayes puts it in The Siren’s Call, one of our most intimate parts of ourselves – our ability to focus attention – no longer feels quite like our own. It has been captured, it feels like, by outside forces that do not have our best interests at heart. I myself would rather not share the number of times that I switched over to my web browser to check Twitter while writing this piece, and while I purposely left my phone elsewhere, I still caught my hand drifting to my pocket to check a phantom phone at least once.

Now, none of what I’ve just said is terribly groundbreaking or original. You can find it in Chris Hayes’ The Sirens’ Call, Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism, Anna Lembke’s Dopamine Nation (all of which, for what it’s worth, I recommend), and a host of other works of cultural criticism or popular science.

But I want to suggest that this analysis should be of grave import for Christians, because the Christian life is fundamentally about attention – and the current highly capitalized attempts to capture and mine our attention therefore are an attack on the Christian life.

What do I mean by this? One way to describe the Christian life is about being moved by the Spirit from an obsessive focus on oneself and one’s desires (Luther’s incurvatus in se) to paying attention to God and to one’s neighbour. To be sure, the Christian life doesn’t end with paying attention alone – it’s really about loving God and neighbour. But attention is the precondition of that love. You could do worse for a definition of prayer than paying attention to God. And the Good Samaritan couldn’t care for the man he found beaten and left for dead on the Jericho road if he didn’t first pay attention to him. Christian life may be about more than paying attention rightly, but it’s certainly not about less than that.

If the Christian life is about attention, this means that our current age of technology-driven distraction, of ever-nimbler attempts to seize our attention, has very real consequences for Christianity. Simply put, by seizing our attention (often, it feels, against our will), it makes it more difficult for us to pay attention to God and to our neighbour. I know I’ve felt this to be true. While I don’t check my phone during worship, I’ll admit that I usually find myself, along with my pewmates, quickly whipping out my phone to check for new notifications as soon as the service ends rather than spending time reflecting in prayer on what I have just heard and received or chatting with the embodied human beings just a meter or two away from me. And in the middle of serious conversations, I’ve from time to time felt a little itch at the back of my mind, a desire for a quick dopamine hit from Twitter or the like. These are ways in which my ability to attend to God and neighbour are degraded by the attention economy.

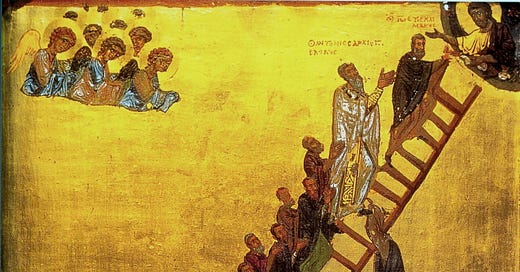

Now, of course, this isn’t really a new problem. It has always been hard to pay attention to God and neighbour. The Christian tradition has spent a lot of time reflecting on how to help Christians to avoid boredom or distraction and really focus their mind and their desires on God. One thinks of Augustine’s Confessions, which is really one long narrative about how at last Augustine overcame the distractions of wrongly directed desire to attend to the living God, or about the eastern monastic emphasis on apatheia, less a total absence of feeling than a sort of lack of distractibility, or the role that Vanity Fair plays in Pilgrims’ Progress, to give just a few of countless examples.

But it is a problem that is facing us in new ways, with the best of human ingenuity currently being deployed precisely to make it harder for us to attend to (and thus love) God and neighbour in an undistracted way. This might sound a little over the top or crankish, but I think it follows necessarily from the analysis I’ve been offering. It’s not that it’s intentionally aimed at this, that Meta or Tiktok engineers are sitting in their offices thinking “let’s make it harder for Christians to pray.” But their attempt to monetize our attention has, I think, exactly this effect.

What does this mean for us? I don’t think it means that everyone has to get rid of their smartphones, although I’ve considered it for myself. I don’t necessarily think that we need to abandon social media en masse either. But I do think that we need to engage with these technologies, this media environment, with a lot more care. We need to recognize that these platforms and technologies are not neutral, that our ready addiction to them is not accidental but by design, that they are set up to make our Christian life more difficult. And I wonder how the church can help its people cope with this reality, how it can provide tools to help us resist the capture of our attention and the concomitant deformation of our ability to attend and to love.

And I wonder if there is a sort of evangelistic opportunity here. No one I know wants to spend more time on their phone than they do; nearly everyone I know feels vaguely trapped and dissatisfied by their relationship with technology. We Christians are inheritors to a rich inheritance of thinking about distraction and attention, of a vast treasury of practices for focusing on what really matters. We have the promise that the Spirit of Christ will enable us to move beyond our eternally distracting selves, to stop viewing the world merely as a sort of means of achieving transitory pleasure, to focus instead on God in whom alone true joy is to be found. The point is not that Christianity can be reduced to a technique to ‘achieve mindfulness’ or what have you, or that the promise of Christian life is separable from Christ crucified and risen. But it would be, I think, a good thing if Christians were known as the people who really paid attention to you when you talked to them, who weren’t constantly grasping for their phones.

Hugh of St. Victor talks about the basic human predicament as an inability to attend and love rightly. He calls it “the instability and restlessness of the human heart.” He writes:

the mind that does not know how to love the true good can never be stable. Since it cannot find the object of its longing in the things that it embraces, it always reaches out with its longing, seeking that which it can never attain, and it never rests at peace. From this, therefore, are born movement without stability, labor without rest, running without arriving. As a result, our heart is always restless until it begins to cling to that One in whom it rejoices that its desire lacks nothing and is assured that what it loves will endure forever.

May the Spirit pour the love of God into our hearts, that whatever the distractions and temptations of the present moment we may indeed pay attention to, love, cling to the only One that can satisfy all our desires – and from that attention and love go out to love our neighbours for His sake.

Hi, Ben. Nice to find you here! Followed you on Twitter ‘back in the day.’

"Put the peace of the heart

above everything."

-@Paul Kingsnorth

When I researched this quote, I realized it is probably based on this scripture:

“Keep and guard your heart with all vigilance and above all that you guard, for out of it flow the springs of life.”

Proverbs 4:23 AmpC

This is my third attempt to write a comment here. I'm going to send it now, before it disappears again.