For Anglican Reconfessionalization

This piece, from Earth & Altar I:1, is made available here with the kind permission of Earth & Altar. If you’re interested in more pieces like this, and want to support Earth & Altar’s work advocating for an inclusive orthodoxy in the Episcopal Church and beyond, please subscribe at https://earthandaltarmag.com/subscribe. For those who are eagle-eyed, you’ll note one or two small edits from the print edition.

I have been skirting around the question of Anglican identity in the pages of Earth & Altar for some time now. I have suggested that, apart from the question of their connection to Anglican identity, the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion provide helpful resources for contemporary theologizing. I have argued that construals of Anglican identity, including those linked to particular moments in Anglican history, cannot be deemed to be automatically out of bounds or to be sinful substitutions of human institutions and doctrinal definitions for the work of the Spirit. I have thus far avoided explicitly setting out a vision of Anglican identity, but it is time to lay my cards on the table. I believe that the gift and task of Anglicanism is to be a particular fellowship within Christ’s one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church, in communion with the Archbishop of Canterbury, that embodies a reformed catholicity centered in the historic formularies of the Church of England and their reception.

In using the language of “gift and task,” I mean that this account of Anglicanism aims to simultaneously describe what Anglicanism is and what it should be. It seeks to be a faithful narration of the history of those churches called Anglican. While this story is not the only story that one could tell, I believe it is a plausible account. The language of gift specifically highlights my firm belief that in an examination of Anglican history, we can see the God who showers gifts upon all members of His Church (and indeed all creation!) blessing us, and using our part of the Church as a means of His blessing others. But this account is also prescriptive: it is unashamedly an account of how Anglicanism ought to be, and is decidedly not uncontroversial at that! That is, it is an account of the task of contemporary Anglicanism: what Anglicans today ought to do. In offering this articulation of Anglican identity, I am going against the grain of some significant tendencies in the last sixty years of Anglican thought that have advocated for what Stephen Sykes calls “deconfessionalization,” a move away from particularly Anglican standards in defining and norming the life of the Anglican Communion.[1] This, then, is a plea for reconfessionalization, for taking up the task of deepening our Anglican identity (which we already possess as something given to us) by reengaging with the Anglican formularies.

But before turning to a discussion of the formularies specifically, it is worth dwelling on a few other points of the definition I’m proposing. The description of Anglicanism as a particular fellowship within Christ’s one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church, in communion with the Archbishop of Canterbury echoes the language from the Lambeth Conference[2] of 1930 and from the constitution of my own church body, the Episcopal Church. It highlights the uniting role of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and Anglicanism’s historical connection to the Archbishop and the Church of England more broadly. By defining Anglicanism as a fellowship within the one Church of Christ, it emphasizes that Anglicans of a wide variety of pieties and convictions have consistently avoided attempts to identify the Church in its totality with Anglicanism. We believe that we are a true part, but only a part, of Christ’s Church, and historically have been quite reticent to unchurch others. To be sure, this reticence has been undermined by a focus on apostolic succession, especially in the last century or so, which has led many Anglicans to determine that other Protestant communions are not, in fact, true churches. But all the same, it remains an Anglican charism. Being in communion with the Archbishop of Canterbury or subscribing to the Anglican formularies have never been seen as a sine qua non of true Christianity. As the example of Richard Hooker demonstrates, this was even sustained during the fever pitch of confessional struggle and mutual anathemization in the wake of the Reformation when Roman Catholics, Lutherans, and many of the Reformed had all declared all the others outside the true Church.[3]

Just as the borrowings from Lambeth emphasize shared ground amongst Anglicans of very different pieties, to describe Anglicanism as reformed catholicity is to adopt language common to all parties in disputes over Anglican identity. Alas, while nearly all will happily endorse this term, it takes on so many different meanings that its descriptive utility when used without further elaboration is limited. For some of the Anglo-Catholic party, the “reformed” part of “reformed catholicity” seems to refer only to Anglicanism’s rejection of papal primacy. “Catholicity” then is defined largely as Roman Catholics define it: transubstantiation as the preferred account of Christ’s presence in the Eucharist, a sacrificing priesthood, a vibrant cult of the saints, the centrality of episcopal governance and apostolic succession, and so on. For some of the Evangelical party, the “reformed” label is identified quite strictly with a narrowly-defined Calvinism, and what exactly “catholicity” means at all is less than clear. And then, of course, there is the notorious “via media” definition, in which Anglicanism as reformed catholicism is seen as a sort of mid-point on a spectrum running from Catholic to Reformed (or Protestant). I identify the essence of the church – which is to say, the primary content of its catholicity – with the pure preaching of God’s Word and proper celebration of the Sacraments. This evangelical core is supplemented with the secondary matters of church polity and governance and fidelity to extra-Scriptural tradition. That is, a church is catholic insofar as it holds to the Creeds of the universal Church, preaches the Gospel, and celebrates Baptism and the Lord’s Supper as means of grace, and secondarily insofar as it is faithful in matters of church order or structure. On this definition, Anglicanism is catholic precisely insofar as it is reformed, not in spite of being reformed. The Reformation as a whole, in fact, is properly understood as an attempt to reassert catholicity, not deviate from it. On this argument, to be reformed is indeed the fullest way of being catholic!

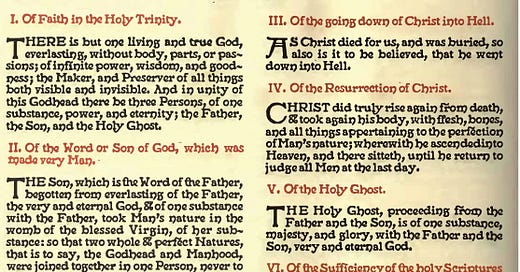

I arrive at this account of reformed catholicity precisely by doing theology centered in the historic formularies of the Church of England and their reception. These formularies are the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion of 1571, adopted during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I; and the Book of Common Prayer and Ordinal of 1662, promulgated after the English Civil War. The Articles provide a statement of faith dealing primarily with issues of controversy during the Reformation, while the Book of Common Prayer and Ordinal set out all the approved liturgies of the church for daily prayer, Holy Communion, Baptism, ordinations, and various other services. In general, they display a moderate, sacramental Reformed[4] leaning, consciously rooted in the Bible and early church. To root Anglicanism in the formularies involves one not only in the sixteenth and seventeenth century controversies that produced them, but also is a matter of being joined to a tradition of the reception of the formularies continuing to this day. The very fixedness of the formularies fostered a rich and varied commentary tradition, comprehending a variety of theological views, from their promulgation to the present day. Commentaries on the prayer book were used to explore its theology, situate it within the history of Christian liturgy, and foster devotion for both clergy and laity. Works on the articles were used in the training of clergy, in the catechesis of laypeople, and in exploring both the central claims and the limits of Anglican theology. Moreover, as the formularies moved beyond England, the questions of how texts associated with a particular national church might rightly be employed in various colonial, and eventually independent, churches became pressing. For decades, resolutions of the Lambeth Conference encouraged Anglicans around the world to adapt the formularies to local contexts while preserving their core doctrinal commitments, and this is precisely what happened.[5] The formularies are a living tradition.

I believe that Anglicanism is best understood (both descriptively and prescriptively) as centered in these formularies rather than strictly bounded by them. Anglican churches have historically been content to allow a fairly wide range of variation in theology and worship so long as the set liturgy of the church was adhered to and the Articles were taught or at least not preached against; even deviations have often been quietly tolerated so long as they do not seek to disrupt the general norming function of the formularies. One can scarce imagine an Anglican arguing, as (for example) some conservative confessional Lutherans have, that there are in fact no open questions in theology about which difference of opinion is permissible. Moreover, more rigorous attempts over the course of Anglican history to use the punitive organs of the state to establish the formularies as strict bounds for teaching – whether during Laud’s anti-Puritan campaigns or the turn-of-the-twentieth-century persecution of Anglo-Catholics – were both unsuccessful and, I would argue, immoral. To argue for reconfessionalization around the formularies is not to advocate for another Great Ejection, especially in those parts of the Anglican Communion that have not historically expected clergy to subscribe to them, so much as it is to seek to establish a particular theological and liturgical grounding for church teaching, authorized liturgies, and seminary training. It is to seek to articulate a center, which precisely in its fixedness can comprehend a variety of relationships to it without falling into a vague comprehension.

Why, then, might one wish to adopt this account of Anglican identity? I offer the following: this proposal allows for engagement with the whole of the Anglican past, aligns us with the formal doctrinal commitments and present practice of Anglicans throughout the world, supports our attempts to heal the sad divisions in Christ’s Church, and, most importantly, is a faithful and edifying interpretation of the faith once delivered to the saints. To begin with the historical question, one problem which besets many accounts of Anglican identity, especially many of those associated with Anglo-Catholicism, is a difficulty in making sense of the history of Anglicanism between the Reformation and the Oxford Movement. Simply put, the first generation of Reformers were decidedly uninterested in anything like ‘Roman Catholicism without the pope’, and even the Caroline Divines, often treated as precursors to Anglo-Catholicism, were distinctly Protestant in orientation.[6] Both before and after the Catholic Revival, the 1662 prayer book (with some relatively minor variations, the most substantial of which was the Scots-American eucharistic prayer) was used faithfully in worship, and the prayer book along with the Articles normed church teaching. Of course, one could reasonably hold that the Reformers, while right in rejecting papal supremacy, drastically overreached until the Catholic Revival set things aright in elaborating an authentic Anglicanism. But such a position often means that one finds little if anything valuable in Anglicanism before 1833 or even the turn of the twentieth century. Ironically, the quest for a traditional, historically-rooted catholicity results in a rejection of actually-existing Anglicanism. The same Anglo-Catholics who criticize Protestantism for attempting to ignore the work of the Spirit over church history by returning to an imagined apostolic past often themselves seek to skip the messiness of Reformation and post-Reformation Anglicanism with a return to an imagined pre-Reformation English Christianity.

An orientation of Anglicanism around a center in the formularies, then, better fosters engagement with the fullness of Anglican history. This does not mean an uncritical endorsement of every aspect of the pre-Oxford Movement Anglican past, nor a rejection of all parts of the Catholic Revival (or, for that matter, contemporary or pre-Reformation Roman Catholicism). We might, for example, reasonably view the elimination of monasticism at the Reformation as an unfortunate overstep, one not required by the Articles’ condemnation of the teaching of works of supererogation (Art XIV), and see its restoration in the nineteenth century as a genuine achievement. But what it does mean is that we do not need to be embarrassed by the Protestantism of our past. We can look for inspiration and conversation partners in writers, church leaders, and theologians of the Anglican past like Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer, John Jewel, John Davenant, Lewis Bayly, and William Beveridge. For those interested in recovering and drawing from those voices largely ignored and marginalized within Christian churches, too, a focus beyond Anglicanism’s Catholic movement is helpful; women were able to eke out relatively more voice in the often-derogated Puritan and Evangelical movements within Anglicanism than in high church or early Anglo-Catholic circles. Anglican history before 1833 is simply more interesting, richer, and more faithful than a historiography which attempts to pick out a few proto-Anglo-Catholic lights in the Protestant darkness allows. The conception of Anglicanism I offer allows an engagement with this history.

Of course, to make this argument risks accusations of offering a sort of ‘British Museum religion’, an account of Anglicanism more concerned with the seventeenth century than the Church’s proclamation of the Gospel today. This is a serious accusation, but I think it misses the mark. Indeed, throughout the Anglican Communion, many member churches find the formularies crucial for their proclamation of the Gospel. It is in fact my own Episcopal Church which is an outlier in consigning them to the vague category of ‘Historical Documents.’ The formularies remain de jure (that is, formal or legal) standards of doctrine for the Church of England and many other provinces of the Communion, as Norman Doe’s painstaking work on canon law across the Communion makes clear.[7] But the formularies often play more than a merely de jure role. While prognostication of the future is always a chancy enterprise, it is striking that articulations of Anglican identity from the Global South in recent years have tended to foreground the formularies as the basis of Anglican identity. To be sure, it is important to note that the conservative group GAFCON, which supports breakaway Anglican bodies across the Anglican Communion, has a particular interest in construing Anglicanism on grounds other than communion with the Archbishop of Canterbury. Without necessarily disparaging the sincerity of those who advocate for it, the construction of ‘orthodox Anglicanism’ around the formularies and opposition to same-sex marriage evidently serves a particular political function. But there is no need to cede the formularies to Anglicanism’s conservatives! Indeed, Global South Anglicans, a moderate-to-conservative body representing provinces from the Global South, has similarly recently held up the formularies as normative for contemporary Anglicanism. Meanwhile, as noted above, the commentary tradition on the formularies continues; scholars like Oliver O’Donovan or J.I. Packer continue to explore the Articles, the Prayer Book, and the Ordinal for the contemporary proclamation of the Gospel. The formularies are clearly neither de jure nor de facto irrelevant to the life of global Anglicanism. It might behoove us Episcopalians to consider at more length why so many of our fellow Anglicans see them as vital for the contemporary expression of the faith.

Changing our focus from global Anglicanism to the Communion’s relationship with other Christian bodies, an Anglicanism generously normed by the formularies has the potential to bear real ecumenical fruit. Along with generally successful Anglican ecumenical talks with Lutheran bodies, the Roman Catholic Church has been a particular focus of Anglican ecumenism over the last half-century, a focus undergirded in Anglican circles by a construal of Anglicanism as one of the ‘apostolic churches’ alongside Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy. However, by this point it has become abundantly clear that prospects at the official level for Anglican-Roman Catholic rapprochement are limited at best. Disputes around ecclesiology, the ordination of women, and marriage and sexuality are unlikely to be resolved anytime soon, and Apostolicae Curae, the nineteenth century condemnation of Anglican orders, has been reaffirmed by the contemporary Roman Catholic Church. Anglican-Orthodox dialogue is at a similar impasse. The account of Anglican identity I’m offering expands Anglicanism’s natural conversation partners beyond Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy towards our fellow traditions of sacramental Protestants descended from the magisterial Reformation, especially Lutheranism, many of the Reformed, and Methodism. The account of catholicity offered by the formularies might help us avoid the anxiety about apostolic succession which has held up attempts at full communion or union with Methodists both in the United States and England – an anxiety that is rather novel and long-contested in any case. We might note in particular that the largest black Methodist body in the United States explicitly rejects the doctrine of apostolic succession, and with it the notion that black Methodist clergy need to have their orders validated by white bishops from denominations which forced them out.[8] An Anglicanism committed to reconciliation with black church bodies will at the very least need to reckon with the way that a commitment to apostolic succession poses problems for our siblings in Christ.

We simply do not need to unchurch our fellow Protestants, even while we may see the historic succession of bishops as a valuable (although not necessary) sign of catholicity which we possess in order to share with our fellow Christians.[9] This position, moreover, is hardly one associated only with sixteenth and seventeenth century Anglicanism. Those of us who are Episcopalians can look to William Augustus Muhlenberg in particular for an example of a nineteenth century church leader who understood the episcopate as a gift possessed by our church for the sake of broader Protestantism, and always avoided declaring other Protestant ministers invalid or demanding their reordination.[10] Particularly in my own US context, it is with fellow magisterial Protestants that I am the most hopeful for real reunion, not (I pray!) on the terms of least-common-denominator vague mainline liberalism, but upon a fulsome embrace of that reformed catholicity to which we are all committed: the Creeds, the example of the early church, Reformation teaching on salvation and church authority. Now, this reorientation I propose does not require an attitude of hostility towards Roman Catholicism or Orthodoxy or an abandonment of our ecumenical efforts there; we can rejoice in our common Christian confession even while being honest about our differences. But it does allow us to orient our efforts towards where they are most likely to bear fruit.

But of course, both the historical plausibility and the contemporary relevance within and without Anglicanism of this proposal for Anglican identity are ultimately secondary to this key question: do the formularies provide a faithful account of the Christian faith? Is an ecclesial community normed around them one through which human beings have the good news of the free gift of salvation in Christ proclaimed to them, are united with Christ in the regenerating waters of baptism, have that union deepened in the Lord’s Supper, and abound in the love of God and good works for one’s neighbor? A full defense in all its particulars (soteriology, the sacraments, ecclesiology, etc.) of the Augustinian, irenically-Reformed Christianity that the formularies teach lies beyond the scope of this piece; at best, for now I can say, “come and see!” I have found in this tradition, at its best, a freeing and consoling commitment to the soteriology of the Reformation alongside an ascetically-sound vision of the spiritual life centered in the Sacraments and daily prayer. I have found an appreciation for the witness of the Church in all its myriad forms, and especially the example of the early Church, combined with a willingness to subject even the most venerable of Christian traditions to the disciplining of Scripture. I have found capaciousness for theological development and appreciation for the various schools or parties within Anglicanism nonetheless normed by a stable anchor more definitive than vague comprehensiveness. It is precisely because I have found such abundant new life here that I plead: let us reconfessionalize!

[1] Stephen Sykes, Unashamed Anglicanism (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1996), xv. [2] The Lambeth Conference is the roughly once-a-decade meeting of all bishops of the Anglican Communion [3] See, for example, Book III, Chapter 1 of Hooker’s Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity. [4] By “Reformed” I simply mean the family of theology and church practice descended from the Swiss Reformation. [5] See here Resolutions 10 and 19 of Lambeth 1888, Resolution 46 of Lambeth 1897, Resolutions 20 and 27 of Lambeth 1908. Even the celebrated definition of the Anglican Communion at Lambeth 1930 includes reference to the Book of Common Prayer, which in this context would have meant the 1662. It is only in the latter half of the twentieth century that the Lambeth Conference comes to abandon the project of defining Anglican identity with reference to the formularies, adapted as appropriate to their local contexts. [6] This is not to say, of course, that every Church of England theologian or bishop prior to the Oxford Movement was a Calvinist! Far from it! But it is worth noting that William Laud, while advocating for a doctrine of Eucharistic sacrifice, took great care to differentiate his own view from that of Roman Catholicism. See here Bryan Spinks, The Incomparable Liturgy: The Book of Common Prayer, 1559-1906 (London, SPCK: 2017), 72. Moreover, the various members of the ‘Durham House Group’ which followed him never condemned the Reformation liturgical and theological settlement in the manner which Anglo-Catholics would. [7] Norman Doe, Canon Law in the Anglican Communion: A Worldwide Perspective (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), 187-240. [8] See, The Doctrine and Discipline of the African Methodist Church 2016 (Nashville: AME Sunday School Union, 2017), 32. [9] The history of the Church of England is instructive here. After the Reformation settlement, non-episcopally-ordained ministers from Continental Lutheran and Reformed churches were regularly allowed to serve in the Church of England without reordination. At the 1662 settlement, it was decided (more with reference to disputes between the presbyterian and episcopal parties within the Church of England than with reference to Continental Protestant churches) that only episcopally-ordained ministers could serve in the Church of England, but this did not require a judgment on the validity of other ministers’ orders. See Anthony Milton, “Attitudes towards the Protestant and Catholic Churches,” in The Oxford History of Anglicanism, Vol 1, ed. Anthony Milton(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). [10] See here William Augustus Muhlenberg, Evangelical Catholic Papers, First Series, ed. Anne Ayres (Suffolk County: St Johnland Press, 1875), especially his writings on the so-called Muhlenberg Memorial.